By nature, I’m an introvert. Yet, when I describe myself as such, I’m usually met by some variation of the same response - Well, I wouldn’t say that. You’re so outgoing, so friendly, and you stack so much paper and get so many bitches. You’re one of the least introverted people I know!

To this, I often reply that flattery will get you nowhere… with most people. But not me.

Now, I understand why I hear this mistaken refrain, again and again. On a societal level, the popular conception of what makes an introvert and introvert and an extrovert and extrovert are warped so violently that they hardly resemble what those words actually mean.

To most folks, an extrovert is the life of the party; if they aren’t constantly surrounded by no less than a hundred different strangers, railing lines of china white off mirror plates in a club and having their inner-ears liquefied by the raunchiest beats a DJ can pump out at 200 decibels, they’re probably contemplating suicide.

Conversely, an introvert, to most’s understanding, is an individual who would rather eat a bullet than place an order at the McDonald’s drive-thru window for fear of making a harmless social faux pas that then requires ritual seppuku to atone for. So much as seeing another person is enough to activate their fight or flight instincts.

Of course, neither of these are true. I think anyone with an IQ north of a glass of room temperature water knows this, but decades of conditioning by the broader gestalt consciousness of what does and doesn’t make an introvert or extrovert still leaves even the most erudite with a distorted view of what the terms mean. Many of us still associate the labels with extremes on either end of the spectrum; introverts are quiet shut-ins, extroverts are raucous party animals.

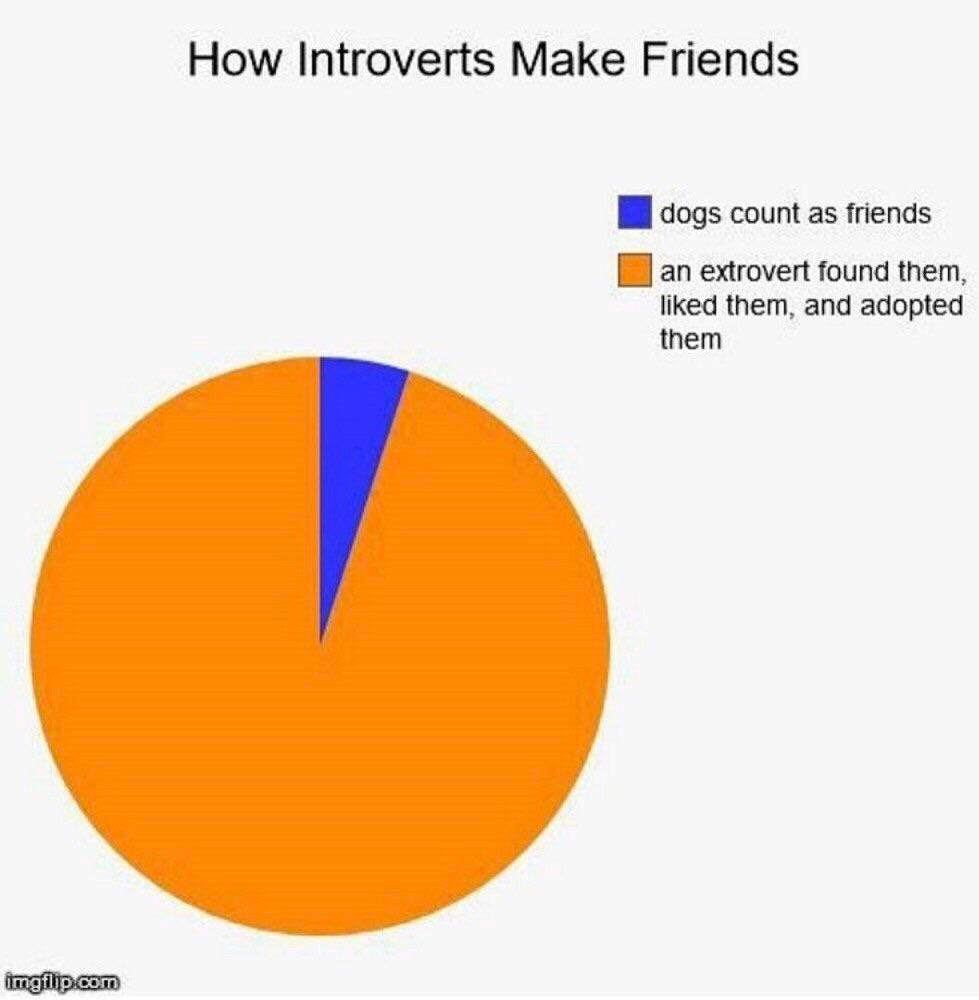

Why is this the case? I believe that, in large part, it’s the general American public’s emotional illiteracy and inability to grapple with nuance. I’d also lay a lot of the blame at the feet of a group of people I can only describe as Proud Introverts. They’re a type that’s probably given to introverted tendencies, yes, but ultimately debilitatingly anxious individuals who thinly mask their self-gratifying peacocking over their own social retardation with tepid jokes.

The truth of the matter is markedly different. Many introverts such as myself greatly enjoy socializing. I’ll admit, I prefer sedate jazz bars or cocktail lounges to clubs (though, I have been known to greatly enjoy a wild setting filled with sweaty strangers, provided the music is to my taste), but nine times out of ten I’ll take a night out with a group of friends to sitting by my lonesome in my living room. Likewise, I know extroverts that prefer much the same settings, and are rather quiet, taciturn people that just enjoy being around others.

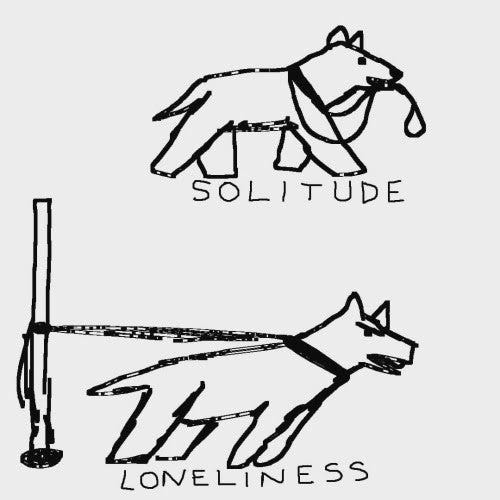

The distinction between the two has little to do with personal taste, and is really much more simple than popular conception would have you believe. The only real difference between an extrovert and an introvert is that the former derives energy from social interactions, while the latter feels energized from solitude. Conversely, extroverts feel drained by solitude, while the introvert burns energy from socializing.

For as much as I do enjoy being social, going out, and spending time with my friends, it is, in essence, draining. I can only go out so many nights before I require a quiet night alone to recharge my batteries, lest I, as the kids would say, risk a crash out.

This is all to say that, for the most part, people need other people. Whether you’re an introvert or extrovert is beside the point; even the most introverted introverts still need human interaction, and those who avoid it in any and all form or fashion are afflicted by social phobias that go far beyond being simply reserved.

I don’t think that so many self-professed introverts are as introverted as they say they are. I believe that they believe they are, but I also don’t think they’d feel the need to justify their self-imposed isolation with masturbatory memes about just how okay they are with being friendless losers.

This ostentatious showboating over just how introverted one might be is behavior I’ve seen on the internet for a long time, especially on Reddit, but it’s swelled in popularity post-Pandemic. It’s no surprise that many Proud Introverts took to social media to run unwarranted victory laps about how well they were handling the lockdowns in comparison to those silly, stupid extroverts, who were no doubt going through violent withdrawl symptoms from being inside for more than two minutes.

Again, anyone who was truly at peace being indefinitely sealed away in their human-sized rabbit hutch by state mandate is not just a standard introvert - they’re mentally ill. The fact that many in this camp were childishly gleeful to see others languish so they could have the state-sanctioned right to live guilt-free in their own personal version of that one OwenBroadcast “Let People Enjoy Things” comic should speak to that.

In my opinion, what these people want to be are American hikikomori. If you know what a hikikomori is, then you know this is not something anyone should want to be.

For those unaware, hikokomori is a Japanese term used to describe a Japanese social phenomenon in which an individual completely retreats from society. The term itself is a compound word derived from the Japanese words for hiku - to withdraw or retreat - and komoru - to stay inside. The term itself seems to have been coined, or at least popularized, by psychiatrist Tamaki Saito, who wrote the definitive book on the subject by the apropos title of Social Hikikomori: Adolescence without End in 1998. The name refers to the fact that many hikikomori exist in a state of arrested development; they don’t work, they don’t leave the house (save perhaps a late-night run to the nearby konbini for food), and typically preoccupy themselves with internet activities, video games, anime, and other such media, most often but not exclusively on the largesse of their parents.

Saito, along with other Japanese psychologists that studied the phenomenon, originally emphasized that they did not believe the condition to be a form of mental illness, but rather a response to then-current Japanese socio-economic conditions. Even the Japanese Ministry of Health echoed this sentiment when they described hikokomori phenomenon as psycho-sociological rather than a psychotic condition akin to schizophrenia or a psychological disorder like depression.

To an extent, I don’t think Saito or his peers are entirely incorrect in this assessment, neither do I believe they are completely correct, either. Though there has always been those who have chosen to withdraw from society for whatever reason since the first cavemen decided to live by one another, the hikikomori phenomenon began in earnest during the early 90’s when Japan’s post-war economic supernova came to an abrupt and violent end with the popping of the Japanese Asset Price Bubble. Though the various causes and effects of this crash are complicated and many, it can be succinctly defined as the Japanese market engine stalling out mid-flight, leading to a period of economic stagnation that the country has yet to work its way out of a full thirty-five years later1.

The natural result of this stunted growth was the rapid erosion of what the Japanese call Shushin Kyo - Lifetime Employment Model, in English - in which an individual is hired by a company out of college and could reasonably expect to remain employed by them for the rest of their career. Though the United States suffered a similar upending of traditional employment models throughout the late 20th century, the shift was much more gradual. In the highly-competitive and strictly traditional Japan on the early 90’s, the sudden proliferation of hikikomori across the country could be seen as a knee-jerk response by young people to a sudden and radical change in society, where many had the expectations of what their future would be, hard-coded into them from an early age, yanked out from under their feet seemingly overnight.

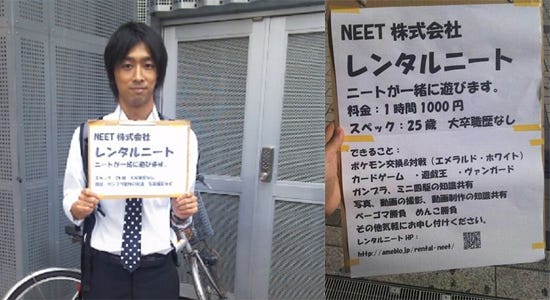

With Japan’s economy currently limping along at a much diminished state2 with no real resolution in sight, it shouldn’t be a surprise that the number of hikikomori has only swelled since the turn of the century. Estimates vary wildly, but the common consensus from various researchers and government organizations cite that the number of hikkikomori in Japan could be anywhere between 1.5 to 2 million and counting. And that’s a conservative estimate. If it’s accurate, that number translates to approximately 2% of Japan’s entire population. This is not counting those who engage in adjacent phenomena, including NEETs, Freeters, and Net Cafe Refugees. For thoroughness’s sake, let’s define these terms.

NEET: A term originating in the United Kingdom as an acronym for Not Employed, Educated, or in Training, referring to an individual who is… well, not working, being educated, or training for any potential career. Though there is overlap between the two, the chief differentiating factor between NEETs and hikikomori is that not all NEETs are shut-ins or shun human interaction. For instance, I found that there is apparently an entire cottage industry of NEETs who will rent out their services as listless drifters, and for the low, low price of a thousand yen per hour, you, too, can have a NEET follow you around. Why? I dunno. This is the same country where you can rent an ojisan3 for similarly inscrutable reasons. But I have to commend the grindset. Very sigma-minded of them.

Freeter: A Japanese term that refers to those under the age of forty who are either under-employed (i.e. fast food employees, konbini cashiers), work part-time, or generally have unreliable, unstable employment, lacking the traditional benefits of full-time employment (i.e. paid time off, health benefits, etc.). Ironically, this term predates the asset price crash of the 90’s, and had been previously enjoyed a positive connotation, with these non-traditional career paths in service or retail industries seen not as under-employment but as a potential new path towards prosperity for the youth.

Japanese konbini are fucking amazing, though. You haven’t lived until you’ve cured a night of drunken debauchery with a black coffee and famichiki for less than three dollars. Net Cafe Refugees: Also known as the cyber-homeless, Net Cafe Refugees are homeless individuals in Japan with no fixed address, who use 24-hour internet or manga cafes as temporary housing. Private cubicles or rooms in these establishments can be rented by the day at generous rates. To accommodate this growing need for temporary housing, many of these establishments also offer complimentary food and drinks as part of the rate, free access to showering facilities, lockers to securely store personal belongings, and sell personal hygiene products4.

Though these are all separate sociological phenomenon, there is significant overlap between them. Most, if not all of them, stem from Japan’s stagnant economy. Many rely on familial support to finance their lifestyles. A not-insignificant proportion of them, hikikomoris not withstanding, are socially reclusive.

To bring this back to Tamaki Saito, he has since revised his stance on hikikomori-ism as a mental illness, if only because if it truly isn’t one, it often engenders them. For obvious reasons, prolonged isolation proves a potent breeding ground for debilitating dysfunctions and disorders; depression, anxiety, anhedonia, extreme emotional dysregulation, are common comorbidities that accompany protracted periods of isolation. Though medical literature correlating extreme isolation with the development of psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia is wanting, it has definitively been linked to auditory and tactile hallucinations, paranoid delusions, and severe degradation in social functionality. I don’t think you need a doctorate in psychology to understand why one might lead to the other.

One of the most visceral depictions of the toll such a lifestyle can take on the human body and mind is the anime series, Welcome to the NHK. The story begins with the hikokomori protagonist discovering that the Japan Broadcasting Corporation5 is engaged in a conspiracy to keep him trapped in this vicious cycle of isolation and self-abuse… because his home appliances “come to life” and tell him as much.

Throughout the course of the narrative, the protagonist’s mental maladies and degraded social capabilities, exacerbated by years of isolation, lead to brief but destructive dalliances with drug, alcohol, video game, internet, and anime addiction, obsessions with disturbing sexual paraphilia, as well as monetary and religious scams, all of which are aided and abedded - sometimes unknowingly - by a cast of equally unwell individuals.

Though the series is a comedy, the humor is black as black can be; it’s a sick, albeit realistic depiction, of self-destructive people, and the vicious feedback loop they tend to draw others in their orbit into.

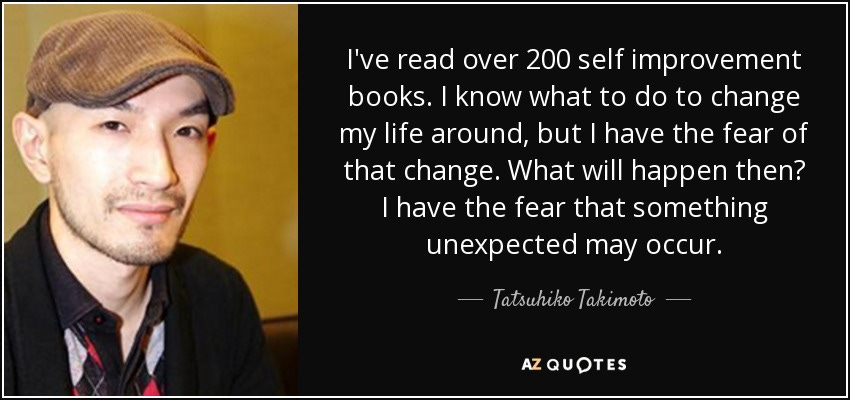

Welcome to the NHK as an anime is actually watered down from the source material; the manga adaptation, and the original novel series that both are based on are even more dark, more disturbing, and, worst of all, serve as a semi-autobiography of the author, Tatsuhiko Takimoto, who himself spent years as a hikikomori6.

He’s said that, in a way, writing Welcome to the NHK was a form of therapy to help him work his way out of the pit of isolation he’d trapped himself in. Did it work? Well, I’ll let him speak for himself with this line from the Second Afterword he published in 2005, three years after the first novel was published.

I highly recommend you read all three of his “afterwords” linked above; you’d be hard pressed to find more authentic insight into how difficult it can be to work oneself out of a living nightmare of their own creation.

Frankly, these Proud Introverts who act as if it’s cute to be some sort of social hermit, or strut about Reddit as if rotting away on their couch, melting their brains on social media and Netflix, makes them superior to people who have friends that don’t require a screen to talk to, make me nauseous.

Part of this is because I’ve had my own periods of extended and unwilling isolation. There were times during them that I believed that it was what I wanted, but that was all self-deluding as a coping mechanism; I hated every minute I sat there in front of my computer, too anxious to call up the people who had extended a hand of friendship to me, too depressed to leave my room, and, frankly, too self-loathing to believe I deserved anything better. That isn’t behavior that should be seen as anything other than abhorrent and in dire need of correction.

Part of this is also because… well, for years, now, I’ve seen think-pieces written by both small and large publications on the hikikomori phenomenon, hand-wringing on when it may arrive on American shores, as if it were some virulent, airborne plague. The truth of the matter is that it’s been here for some time, now; we just lacked the vocabulary to identify it, or the chutzpah to just up and admit that it’s already taken root.

Let’s go back to what gave rise to the hikikomori. The Japanese authorities, perhaps characteristically, seem to want to ascribe the roots of the hikikomori in a very clinical, analytical way. The economic crash and subsequent economic stagnation was the action, and the hikikomori was the reaction. Again, that’s not untrue. But more than simple economic prospects were lost in the crash of ‘90; what the Japanese youth lost, more damningly, was hope. Hope for a better future. Hope for prosperity. Hope for the basic building blocks of a good life for most people - a stable job, a home, a family.

I don’t need to tell you that hope for a better future is something in short supply for a vast amount of Americans under the age of forty. Most of that age cohort has only seen this country degrade since the towers went down that day in September over two decades ago. Financial catastrophe after financial catastrophe, a seemingly impenetrable job market, political dysfunction of the highest order, housing that’s unattainable short of an unexpected lottery win, complete and total social atomization; the kindling for a generation of American hikokomori has been laid thick.

But it’s important to remember that the hikokomori and similar groups in Japan are still an underwhelming minority. It’s a growing minority, yes, and 2% may be an astounding fraction of a population, but it is still just that - a fraction. Most Japanese, regardless of generation, still grew up and are maturing to become functional, productive members of society.

One of the most striking experiences I had while visiting Japan happened in the city of Kobe.

Most people, both locals and expats, were confused as to why I, as a tourist, would even bother stopping there when there were so many other places to go. The truth of the matter is that I didn’t intend to stay in Kobe as long as I did, but out of everywhere in Japan I visited, I liked it the best. There’s no shortage of things to see, things to do, the locals were by far some of the warmest I met while traveling, and there was no shortage of small, eclectic little places to drink and catch live music7.

But, I do understand why so many people I met there were puzzled by the fact I opted to stay in Kobe for several days when most would never think to visit. With a population of around 1.5 million, situated thirty minutes from the bigger, brighter, and flashier Osaka, Kobe is often relegated to a second-tier city. It’s effectively San Diego to Osaka’s Los Angeles.

While I was there, I noticed something curious as I walked about the main nightlife drag of Sannomiya - it was packed. It was a Wednesday night, yet people were everywhere. Young people, at that. You couldn’t throw a stone without hitting a group of twenty-somethings sitting on a bench, a table, or just on the side of the street, eating and drinking and generally having a good time. This was something I might have expected in Tokyo or Osaka, but it was the general state of affairs almost everywhere I went. Hiroshima, Odawara, Kyoto, Shizuoaka - all of these supposed B-Tier cities had night life that blew any American city out of the water. The streets were thronged with young people. It was difficult to find places to drink or eat that weren’t filled to capacity, even late into the night. Half the time, I only got into a place because I’d have a recommendation from someone at another establishment, and dropping their name proved to be a miraculous way to free up a seat in an otherwise packed izakaya or bar. Not every Japanese person was overly friendly, but pretty much every where I went there was always someone willing to talk. Or try, since the average Japanese has next to no grasp on English outside of yes, no, and thank you8.

This isn’t to say that every Japanese citizen is a social butterfly. I’m well aware that for everyone I saw out on the town, there were probably three or four that were sitting at home watching the boob tube or doomscrolling on their phone. I’m under no delusion that it isn’t a country suffering from it’s own crippling systematic issues. But no matter where I went in Japan, the cities and towns and even the people were lively in a way that I have just never seen in America.

I can’t tell you the last time I saw a group of young people out on the town in America. I moonlight as a bartender at several places and frequent even more watering holes, and I don’t think I’ve ever seen a group of people under the age of thirty just out for a night on the town. Even my town’s resident club is usually packed with people who, if they aren’t thirty, they’re getting close. When I do see young people out - and I’m stretching the definition of the word young, here - they’re bands of Millennial women who basically operate in a phalanx; they don’t talk to anyone, they don’t want to meet anyone, and if anyone outside their cadre does try to engage with one of them, they close ranks and shut them out. Going out for a night on the town doesn’t seem to be a social activity for Millennials so much as an excuse to get schlitzed in a place that isn’t home.

This isn’t really surprising, all things considered. If any generation is taking to the concept of hikikomori-ism, it’s the Zoomers. Zoomers drink markedly less than preceding generations. Many don’t go out. Almost half of them have never asked a girl out in their life or been in a relationship, and though the number varies depending on the source, upwards of three-quarters of them are single. Two thirds of them also report struggling with loneliness and making friends. They’ve gained the unsavory sobriquet of the Stay at Home Generation not just because the majority still live with their parents (through no fault of their own, due to rapacious rent prices across the countries), but because they simply, by and large, do not do much outside of their living spaces.

And, don’t get me wrong, this is a bigger issue than just them damn kids don’t drink no more! It’s not that a majority of younger people aren’t going out like previous generations, but rather that they’re just… not doing much of anything, really.

These are issues that I think can largely and easily be linked to the fact that many Zoomers just don’t go out and socialize, or really engage with the world much beyond their own screen9. Now, this isn’t a struggle session for my younger friends. For one, Millennials aren’t exempt from any of this and our statistics are nothing to brag about, either. For another, it didn’t take much thought on my part to identify why Japanese Zoomers and Millennials are going out while their American peers aren’t.

It’s a money thing. In an economy rife with inflation, a job market that’s in the gutter, and a youth unemployment rate that could very well be ten percent, I can’t blame Zoomers - who by and large are not working well-paying jobs - aren’t spending what little discretionary income they have on overpriced cocktails, cover charges, and most “affordable” watering holes are not places most respectable folks want to be. Conversely, food and drink are two things that are relatively cheap in Japan. This can be extrapolated to hobbies as a whole, most of which require some sort of monetary investment that may or may not pay off.

It’s a time thing. For those who do work, time is a resource that many are not flush with. The average American works more than eight hours a day when factors like commutes are counted for, and when basic necessities such as shopping for groceries, house upkeep, and other such things are thrown into the mix, very few have the excess time and, more importantly, energy, to burn on social functions. Interestingly, during Shinzo Abe’s push to root out the causes of Japan’s declining birth and marriage rates, one of the most consistent answers provided by singles was that they lacked the time to even meet a romantic partner, let alone spend time building a relationship with them.

It’s a lack of third spaces. Much ink has been spilled on the systematic destruction of third places in American society. Many of the places that people used to go to socialize simply don’t exist any longer, and those that still do often require some kind of monetary investment to justify being there (i.e. a cafe, a restaurant), or people just aren’t going there to socialize (i.e. it’s awful hard to hit on that cute girl in the corner seat when she’s got her headphones in and clearly does not want to chat). There are also loitering laws that exist in America that keep people from congregating in public spaces that Japan doesn’t have. Which, unfortunately, isn’t completely unreasonable, since in America, we have a very stark issue that Japan doesn’t…

It’s a crime thing. Now, Japan is not some perfect utopia free from crime. Crime still happens. In fact, it probably happens more than the Japanese authorities admit it does; there’s reason to believe that the crime rates in Japan are manipulated to appear lower than they really are. But, even if that is the case, it still boasts a tangibly lower crime rate than the United States. When I stumbled back drunk to my hotel through Osaka’s Namba district at four in the morning, despite being surrounded by prostitutes and their very obvious criminal handlers, I never felt as if I was in danger of being dragged off into an alleyway and looted like a low-level RPG baddie despite being in the one place it was most liable to happen.

Pictured: Me trying to find my hotel through all the BLINDING LIGHTS. I distinctly remember walking through the quieter parts of Shibuya at two in the morning and thinking, You could not do this in Seattle. You should just couldn’t, unless you wanted to risk losing your wallet or your life. There’s a reason that Japanese salarymen can black out in a fucking alleyway in Tokyo and remain untouched all night, and why I won’t even get close to Third and Pike in broad daylight. No one wants to take the train into the city for a night of pub crawling, a concert, or any kind of public event when they’re not confident they won’t get stuck for their watch on the return trip.

It’s the internet. It’s as simple as that. Why would a broke Zoomer (or Millennial) go out and spend money they don’t have to speak to people they may or may not like when they can fire up the PC and hop in a Discord chat, play video games, or just mindlessly scroll through social media? It’s a hollow placebo - the body quite literally releases different hormones when you communicate via text, voice call, or even video, than when you speak face-to-face with someone. But, like a run to the border for some Fourth Meal, it doesn’t actually do anything good for you, it isn’t really all that satisfying… but it’s better than nothing. I guess.

It’s a culture thing. I could dig down deep into this one, but, to be concise, I genuinely think that part of the American youth’s reticence to go out and socialize in public is a knock-on effect of the lockdowns. Being forced to remain at home for months, if not years, in some cases, no doubt reinforced utilizing the internet as their de facto means of socializing.

This list is by no means comprehensive, it’s just the most obvious factors that leapt out at me after about five minutes of consideration. I know for a fact these are qualities that afflict Millennials, being one myself, but if you’re a Zoomer and you’re reading this, please, feel free to offer your own input; I’m on the outside looking in relying on my own anecdotal evidence and those provided to me by my Zoomer friends, many of whom distinctly don’t fall into the camp of neo-hikikomoris. How else would I have met them if they didn’t frequent where Oldhead Uncs like me waste our time chatting shit?

Whatever the case may be, I believe we’re staring down the barrel of a genuine societal crisis, if we haven’t already been grazed by the first bullet. Japan is a country with bountiful third places where young people can gather without fear of being victimized by a violent thug, yet the number of hikikomori only continue to grow, year after year. Hell, they even admit that it’s a problem, and one that’s only going to intensify as their population continues to shrink and economy contracts.

In America, however, no one’s really talking about the fact that not just the youth, but every demographic is taking a turn towards the insular. It’s only fringe commentators who seem to acknowledge that we have increasingly few places to go and an ever-dwindling list of things to do as the public space is gnawed away or pay-walled at every angle, effectively funnelling many into subscription-based ghettos accessible through a screen. And, like most issues we face, I’m sure if anyone in a position to do anything about it did say as much, they’d follow it up with, But it’s a good thing. And, sure - it might be good for companies like Netflix and DoorDash and all the other corporations that actively gin up sky-high profits off the nascent population of stateside hikis.

But does it benefit anyone else? And more presciently…

Does it really have to be this way?

In Japan, the 90’s is widely known as The Lost Decade, referring to the near net zero growth experienced in the economy. When this trend did not change in the 2000’s, it was changed to The Lost Two Decades, and then again as The Last Three Decades when the economy failed to grow during the 2010’s. If trends continue at pace, we’ll be looking at The Lost Half Century soon enough.

Literally just as I was leaving Japan, Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba made the statement that Japan’s economic situation is more dire than Greece’s. The country was also beginning to ration and raise prices on rice - a rather important staple of the average Japanese diet - due to shortages. The weeaboo’s utopia it is very much not.

A term for middle-aged men or Uncle, tantamount to Unc in AAVE.

In Mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, a similar phenomenon called McRefugees has arisen, where homeless individuals utilize 24-hour McDonalds and other such establishments as temporary housing. There’s even a Hong Kong-produced film about the phenomenon humorously titled I’m Livin’ It.

In Japanese, the Nippon Hoso Kyokai, thus, the NHK.

I can’t say I recommend Welcome to the NHK in any iteration due to just how unrelenting depressing and dark they are, but they are, in my estimation, all very well-made and worth watching/reading. Provided you’re able to digest them.

Apparently, Kobe is considered the entry-point of Western music in Japan, owing to it’s long history of being one of the few Japanese ports with international ties, resulting in a robust music scene.

That one AI translator app was actually incredibly useful and made it possible to have long and meaningful, albeit clunky, conversations.

And please, before you begin to rattle off exceptions, yes, I know - it’s not everyone, but I’m speaking generally, here.

Y2K Zoomer, here. I usually hate “so-and-so here” comments, but I thought I might give my two cents. And I’m doing pretty good, all things considered, but this generation was definitely sold a false bill of goods in life.

Life has pretty much been a series of disappointing milestones. Everything people told me I’d do as I grew older failed to materialize or gave underwhelming results—college, most of all. The things I enjoy and succeed in are things nobody ever told me were going to be important or that I should invest time in doing.

I make a point to try and pursue my hobbies and be my own person, and it’s definitely set me apart from my peers in an uncomfortable way. I write, I burn CDs, I listen to opera music, I didn’t use SnapChat, and I have never installed TikTok and hopefully never will. Even at the peak physical and social condition of my life, it’s never been enough to make other Zoomers look up from their phones and break the ice with me. People don’t approach me, and if I approach them then it’s pretty much a given that I’ll never be able to compete with that abominable Apple scrying-mirror.

In fact, I don’t really see any Zoomers at all. I have no idea where they went. I had a single semester of college with them before COVID hit and then they all scattered like cockroaches. Now that I’m out of college, I don’t think I’ll ever see another twenty-something again until the iPad babies grow up. Everyone out in public is old, everyone at my job is decades older than me, everyone you see sitting sulkily in their car at rush hour has grey or greying hair. I live in a big city (for Great Plains standards), but they’re nowhere to be found here. I suspect they may have all moved to Dallas-Fort Worth and I alone was left behind in Oklahoma.

All things considered, I’m pretty socially active and have a lot of friends that are able to provide incredible amounts of support for me on a moment’s notice. But all these friends are ten years older than me, and almost all of these I met at Church. If it wasn’t for the Eastern Orthodox Church, I would genuinely have zero social contact with people outside my family. The dying embers of high school friendships are impossible to rekindle, and COVID killed any chance of socialization at what was already a socially-quiet college at the best of times. Snapchat and TikTok delivered the fatal blow.

I am not one of the men who checked out and gave up on life. But it does often feel like life checked out and gave up on me. Excuse me for writing a whole book here on you—but I’d have to say that your assessment of the extreme social challenges Gen Z faces is spot-on.

Not going to lie, when I saw that title I thought this was going to be the Chris-chan post and braced myself for a swift slide down into that particular abyss. Anyway, interesting, and a good antidote to the usual stereotypes about the Japanese. Your intro/extrovert distinction also makes sense. Reminds me of one of the most charismatic and outgoing people I ever met, who was also almost obsessed with getting as far away from people he could, spending more time in the woods than anything if he could help it.

Digression, but the "lost decade" counter is kind of funny, in the sense that it shows how absurd the whole idea of eternal economic growth is. They're chasing an old normal that's just not physically possible, and like JMG says, where Japan is at is where we're all going. To be honest, I'm getting kind of sick of the pretense. It'd be so refreshing if we could just admit the 20th century growth economy is never coming back, and shift focus to gradually building down modernity in as controlled a manner as we can. (Chris Smaje is one of my other favorite writers who goes into great detail with all this: https://chrissmaje.substack.com/)

I think one very important takeaway here is that so much of our cultural mythology (or what Greer calls "the myth of Progress") is based around the idea that every generation is going to be better off materially than the last one as a matter of course. Like you said here, this idea is clearly failing all around us. That's going to lead to some jarring changes. Or: is there any way we can unhook the sense of "hope for the future" from the need for ever growing material consumption, while also recognizing that the currently existing economic goods are very unfairly divided, and that a sane society should offer its young people some way to have independent family lives? (Though maybe not quite so independent as we're used to...does it really make sense to have each generation completely uproot and create a whole new household from scratch in another place, complete with a mountain of material trappings?)

As for "third spaces", I was surprised you didn't bring in the "Bowling Alone" book, which IIRC talked about many of these issues in the early 90s before the internet. I'll admit I haven't actually read it (one of those things I never got around to), but I know it's a classic in this field.

Also appreciate hearing from the Zoomers here in the comments. Interesting perspectives for sure.