1917 was not a pleasant year for a good many people in Europe. Entire swathes of France had been converted into cratered and corpse-choked mud-flats. In two days, between April 16th to the 18th, over 30,000 Frenchman would be slain in the opening overtures of the ill-conceived Nivelle Offensive. By May, the casualty count would reach the gruesome milestone of 100,000, resulting in a series of mutinies that threatened to completely dissolve the French military. The seas became the hunting grounds of German u-boats, which had been given the green-light by the Kaiser to turn any sea-going vessel larger than a canoe into scrap metal. In the South, the Austrians proved that they were not completely inept - with a little help from their German friends and their new-fangled weaponized gas - by striking a fatal blow to the Second Italian Army at Caporetto, triggering a full-scale collapse of the then-ruling regime in Rome. Though the Italians would find their footing again at Monte Grappa, the Italian Front would become a nightmarish, mile-high battle above the clouds in the freezing peaks of the Alps, where the biggest hazard to a soldier’s life was not enemy combatants, but unsteady footing and ice.

Similarly, the Russians were forced to bow out of the war entirely after the disastrous failure of the Kerensky offensive. Unfortunately for all parties involved, the German-planted time-bomb that was Communist agitator, Vladimir Lenin and his Bolshevik Buddies, would detonate in October of that year, ensuring that the horrors of the Ostfront would not end, but simply take on a different, perhaps even more destructive form that would ultimately end with seven to twelve million Russians dead by 1922.

Meanwhile, the British had turned their attention to the Middle East, shifting their focus from invasions of Anatolia to a bitter war for the Holy Land with the ailing man of Europe in Istanbul, who was proving to be not as feeble as previous thought.

As far a field as the seas of the South Pacific and the dense, dark jungles of Sub-Saharan Africa, the Great Powers of Europe were engaged in wholesale slaughter of both themselves and their colonial vassals. Though everything appeared to be turning up Milhouse for the Central Powers (except the Turks, who were meeting considerably mixed results in the Middle East), the winds of change would begin to blow from the West across the Atlantic.

Even though the slumbering Anglo giant of the new world had not started the war, they were preparing to bring an end to it.

But it wasn’t all bad for everyone, everywhere. Yet.

In fact, for a pair of British girls, 1917 would be the one of the most exciting years of their young lives.

That was the year they started a joke.

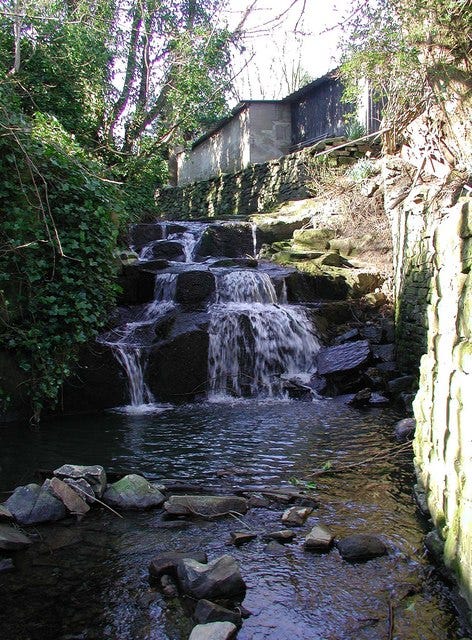

At the age of eight, nine-year old Frances Griffiths and her mother left Cape Town, South Africa, to return to the Great Anglo-Saxon Mothership of Albion while her father - name unknown - was shipped to the ongoing catastrophe unfolding across the English Channel. Upon arrival, they traveled to Cottingley - a humble, picturesque village situated in the rolling hills of West Yorkshire. There, they would find lodgings with Arthur and Polly Wright, the latter of which was the sister of Frances’s mother, Annie. The Wrights had a daughter of their own named Elsie, who was, at the time, sixteen. Though significantly older than her cousin, the two girls appeared to get along swimmingly. The two would often disappear for hours on end, when Elsie would take her younger cousin down to a small stream, known locally as a beck, that ran by the Wright’s property.

Neither Annie Griffiths or Polly Wright were too fond of the girl’s little play-dates down by the lazy river. They didn’t much appreciate them coming home in soaked clothing, wet shoes, and tracking mud through the house. One day, after being forbidden from playing down in the beck, wouldn’t you know it - here comes little Frances, all wet and messy again. When her beleaguered mother asked her why, exactly, she’d so brazenly disobeyed direct orders from the unquestionable authority of Mama Said, Frances gave a rather unconventional answer.

She’d gone down to see the fairies.

Ah. The ol’ I’ve gone to prance with the fae, dear mother, excuse. Who among us haven’t heard that one, or perhaps tried to sell it to our own parents? Why, when I was a wee one, my hysterical mother would demand to know where it was I disappeared to during the night when she’d come into my room and find my Pokemon-branded bed sheets unoccupied. I told her that I’d simply slipped through the window at the behest of the pretty young lady with the honey blonde tresses who lived in the nearby woods - she was very insistent that I come play with her and her many small friends in the silver light of the moon-dappled glen. Forever.

Forever was quite a big ask, so, obviously, I ate my fill of sweet fairy delights, got my groove on with some comely dryads, hit a little bit of that pixie kush, and went on my merry way.

Of course, my mother, just like Elsie’s and Annie’s, was convinced that I was blowing smoke from that pixie-pack good-good up her proverbial derriere.

But I wasn’t.

When this answer was met with understandable disbelief by Frances’ mother, Elsie stepped in to claim that, oh, no - there were fairies down in that there beck. She would know. She’d seen them, too. Given that Elsie was, y’know, old enough to drive1, pretty much everyone had the same reaction to her claim.

But Elsie was adamant. There were fairies down in the beck. And, by George, she’d prove it. She’d take a picture of them.

Now, I never had the idea to go try and snap a selfie with my fairy godmother and all her diminutive, winged friends, but Elsie and Frances were much less willing to allow their honor to be wrongly besmirched. Elsie petitioned her father - an avid amateur photographer who not only had cameras, but his own darkroom to develop photos in - to allow her to borrow a camera so she might find some photographic evidence that she and her cousin were, indeed, big chillin’ with the preternatural. No doubt amused by the absurd request, Arthur granted his daughter use of a Butcher and Son’s Midg quarter-plate camera, which looks like this.

Now, I cannot imagine entrusting what appears to be a rather troublesome and wily sixteen year-old with a piece of equipment that I imagine must have cost a small fortune at the time so she might snap some pictures of pixies - around water, no less - but Arthur relented.

Camera in tow, Elsie and Frances walked down the beck.

Neither of them could have known that what they were about to do would set in motion a series of events that neither of them would be able to outrun for the remainder of their lives. Quite literally, they were about to alter the trajectory of their lives - and others - irrevocably.

Thirty minutes later, they returned, as her father described it, triumphant. They politely requested (read: begged) that he develop the film plate, which, after pausing for the perfunctory cup of afternoon tea like any self-respecting Englishman, he did. This is the resulting photograph.

Now, I’ve read many different variations of this story. In several, it’s stated that Arthur was shocked, and it’s heavily implied that his surprise came from the fact that his daughter had, for the first time in human history, captured certifiable, inarguable, photographic evidence of fairies. And in only thirty-minutes, that that! And, indeed, Arthur was shocked; he was shocked that his daughter genuinely thought he was so stupid that he’d believe that she’d really just become the first person to photograph fairies.

Arthur knew his daughter (as one would hope he would). He knew that she was, like him, keenly interested in photography. He had taught her how to work a camera, develop photos in the darkroom, the whole nine-yards. She was handy with a camera, and had even worked in a photography studio in town for a while, where she’d learned the art of touching up and doctoring photos. He also knew that she was skilled with pen and paper, as well. She liked to draw, and she had gotten good at it over the years, too. Most importantly, he knew that Elsie was not unknown to, as the British say, take the piss. In an interview with Frances’ daughter given to The Daily Express in 2009, Christine Lynch told reporters thusly of her Aunt Elsie:

While Frances was always strictly upright, Elsie never shied from colouring the truth.

Arthur reasoned that his daughter must have drawn up some dancing fairy maidens, stuck them to some cardboard, cut them out, set them up, and sat down Frances behind them all.

Elsie, of course, denied this. So adamant was she that the photo was genuine that, two months later, she took the Midg quarter-plate, marched down to the beck with Frances in tow, and returned with a plate that produced this photo.

Arthur, again, remained unconvinced. When Elsie said that she could provide even more photographic evidence of her fairy pals, Arthur told her he’d had enough of her nonsense; he refused to allow her access to his cameras.

For the next two years, nothing much of note followed. It also seems as if the girls made multiple copies of the photo, either through Elsie’s connection with the professional photography studio in Cottingley or with Arthur’s amateur darkroom, as a copy of Frances’ picture with the fairies accompanied a letter she sent to a friend back in Cape Town.

In this letter, Frances wrote the following:

I am sending two photos, both of me, one of me in a bathing costume in our back yard, while the other is me with some fairies. Elsie took that one.

Gotta love the blithe tone of this one. Yeah, that’s just me. Chilling with the fairies. No big deal. Elsie took it btw.

On the back of the photo, she added the quip:

It is funny, I never used to see them in Africa. It must be too hot for them there.

A real jokester, this one. She would have knocked ‘em dead with a Netflix stand-up special, if she’d been born later.

Now, I might be wrong in the way I read Frances’ quotes, and I may be interpreting the entire chain of events with my own biases, but it seems to me that neither of the girls were taking the matter all that seriously. To me, it seems that they made the photos as a goof and kept playing the act as if it had really happened in a facetious way as a sort of inside joke between them. It appears that the only time the pictures were even brought out of the family photo album to show as a gag for visiting family members.

Oh, hey - here’s Elsie shaking hands with a gnome, haha.

I’m sure they all had a good laugh about it because, I must stress - it really seemed that no one was taking it all that seriously.

Then, 1919 came around.

While Elsie’s father remained steadfast in his assertion that the girls had simply snapped some pictures of themselves with cardboard cut-outs, her mother was not so critical. There seems to be no clear consensus on just how not critical Polly Wright was about the photos. Some claim that she, like everyone else, kind of knew they were a joke, but was willing to humor the idea that there may be fairies that swelled around the beck. There are those who seem to think that, in contrast to Doubting Arthur, Polly was had bought the photographs hook, line, and sinker, and genuinely believed they were genuine evidence of fairies frolicking with her daughters.

Here’s where things get tricky, and a lack of good, first-hand, reliable evidence really begins to muddy the waters.

It seems that Polly was most-likely something of what we would call today a New Ager; if Polly Wright had been born in the early 90’s, she’d be on TikTok making videos about what type of stone to put up your ass to cure tinnitus. Circa 1917, though, TikTok was roughly a century away from coming to fruition and people - even the weird ones - had somewhat more sense than your average New Ager TikToker that thinks being a burned-out former gifted and talented kid with undiagnosed ADHD means that you’re a member of the next step in human evolution. But not by much.

Around 1919, Polly Wright became interested in the Theosophical Society.

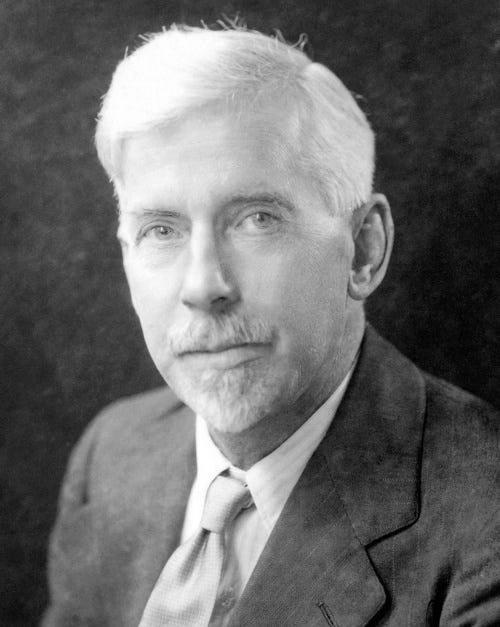

The Theosophical Society was - and still is, since it’s active today - a new religious movement that began in New York City around 1875, started by American Buddhist-convert Henry Steel Olcott and, more infamously, Russian-born occultist, Helena Blavatsky. Here’s how Blavatsky is depicted in the popular Japanese media franchise, Fate/Stay.

Compare and contrast with an actual photograph of a young Blavatsky.

I always just found the fact that Blavatsky was reimagined as a kawaii uguu animu girl in the series supremely hilarious2. I have to wonder how she'd feel about it, were she here to see it.

Now that we’ve all had a nice, sensible chuckle, we can not discuss what the Theosophical Society believes, because, frankly, I don’t really know, and I don’t have the time to do the necessary legwork at the moment to figure it out. They call themselves esoteric, and when they do, they are not exaggerating. It seems as if one of the core tenants of their beliefs is that humanity was (and is) undergoing a sort of spiritual awakening and evolution. Third eyes opening. The Age of Aquarius. That sort of thing. It’s actually a lot like the aforementioned Indigo Children schtick, ironically enough, but the in’s and out’s of Theosophy really aren’t germane to the story at hand. Just know that, at the time, it was getting a lot of attention in both America and abroad, with local chapters sprouting up across England and Europe and attracting the membership of very prominent, very influential people.

Just like how much Polly really believed her daughter had photographed fairies is up for debate, just how interested she was in Theosophy is also unclear. Some will say she was an avid participant in the movement’s local branch in the nearby town of Bradford. Others seem to believe she had just shown up once or twice to hear what they had to say. Short of interviewing Polly Wright herself, which is rather difficult on the account of her being dead, we’ll never really know.

Let’s just say I’m not as certain that she was as much of a true believer as many variations of the story paint her to be. Personally, while I doubt Polly Wright genuinely thought the pictures of fairies were genuine, I wouldn’t doubt that she perhaps had some belief that fairies themselves existed. Again - I could be wrong. But… well, just call it a hunch.

What we do know is that, in 1919, Polly Wright brought copies of the photographs to a meeting of Theosophists in the nearby town of Bradford. Arthur would have been in poor company among them, as it seems that they were far less skeptical than he when it came to the legitimacy of these photos. Probably because they didn’t know Elsie.

Several months later, one of the theosophists that had attended the Bradford meeting brought copies of the photographs to the English branch of the society’s annual conference in Harrogate, North Yorkshire. All of the big names in English theosophy would be in attendance, including one man named Edward Gardener.

This guy didn’t just believe the photographs depicted real fairies. He knew they did. He claimed that, surely, if fairies, which had been seen for untold centuries, were getting comfortable enough to appear on camera, well - the Age of Aquarius or whatever was well on it’s way, and pretty soon we’d all be bebopping around with pixies, gnomes, and probably a friendly wendigo or two. It’d be a veritable monster mash, a graveyard smash, the whole nine-yards.

Gardener reached out to the Wrights and asked if he could have the original glass plates upon which the photographs were taken and developed from. He said in his letter that he believed the photographs were “the best of its kind I should think anywhere.” Which really begs the question was other photos of that kind there were floating around at the time.

Arthur, probably more than happy to be rid of the plates that had been nothing but a headache for him, and most likely wanting this weirdo Gardener to leave him alone, obliged. One must wonder what that night’s dinner table conversation between Arthur, Polly, and Elsie sounded like, and if they didn’t get an earful for just how far their little joke was going.

I don’t think poor Arthur could have had any idea just how much further his daughter’s jape was going to go.

Gardener, in the meantime, sent copies of the photos and the plates themselves to a man named Harold Snelling, who’s only described vaguely to be an expert on photography. How so? Nobody thought to document that, apparently. At least, not on any free sources I could find. One source I found did provide this unattributed quote the Snelling:

“What Snelling doesn't know about faked photography isn't worth knowing."

Since this is one of the the most detailed resource I’ve found outside of Wikipedia, I’m going to give this author the benefit of the doubt that they read scholarly works on the topic I do not have any access to, and I found it in other resources as well, but, still - take it with a grain of salt. Provided the quote is true, however, that’s actually a pretty great little attestation to Mr. Snelling’s abilities.

Snelling’s assessment of the photographs includes the following statement:

However, he did not say what was depicted in the photograph were actually fairies. What he did say was the following: “These are straight forward photographs of whatever was in front of the camera at the time.”

Translation: what you see in the pictures was definitely there… but they probably weren’t actual fairies.

But I doubt he was going to make too much of a fuss about it, since Gardener commissioned him to redevelop the plates and make higher-quality prints that he was going to sell at lectures. If I were him, I wouldn’t have said anything else, either.

This printing bonanza set off a chain reaction which resulted in Gardener showing the pictures to his cousin, who in turn happened to show them to a certain fellow who was very interested in fairies at the time. This individual had been tapped to write an article on fairies for the popular publication, The Strand Magazine, for their rapidly approaching Christmas issue. How very fortuitous for him that, as he was stumped on what exactly to write, these photographs practically fell in his lap.

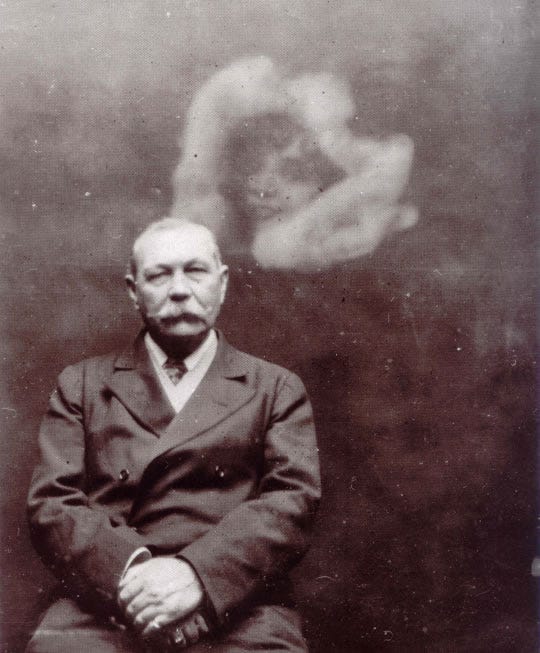

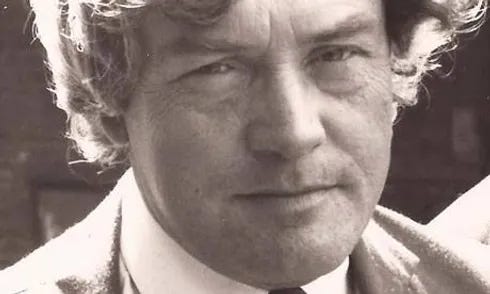

Now, the writer in question - well, you might have heard of him once or twice. He was pretty popular in England around this time, but these days, he’s not really a guy we talk about all that much. Does the name Arthur Conan Doyle ring a bell?

Oh, right - I guess he did write those little Sherlock Holmes books, and all. They’re still making adaptations, spin-offs, and movies about those, I guess.

All joking aside, Doyle’s Holmes heyday was behind him at this point, but he was still one of the most famous and well-respected figures in British literature, and regularly publishing, as the kids today would say, straight fire.

By this point in his career, he was also well known for being, ah… well, do you have an uncle - or perhaps an aunt, it’s not gender-specific - who’s really, really into schizo paranormal stuff? Kind of like me, except they genuinely believe that they may have been abducted by aliens, or that the ghost of their dog still regularly comes and visits them? Yeah, Doyle was like that to the entirety of England. His eccentric interest - no, obsession with the paranormal was very well known, and had only increased as the horrors unfolding on the Continent continued. Doyle, like many, had turned to spiritualism, new age religious movements, and the preternatural as something of a balm for the emotional damage inflicted by the war. Damn near an entire generation of young Englishman - Doyle’s son Kingsley included - had died for King and Country, and, even though victory had been achieved in 1918… well, for many, it didn’t really feel like it, and no amount of victory was going to fill the empty chairs at dinner tables across the United Kingdom. It’s only natural that Doyle and others were very open-minded to paranormal phenomenon, especially that which dealt with life after death and communication with the dearly departed; it gave them hope that, one day, they might see those that left before them again.

Doyle was immediately struck by the images presented to him. To him, they were sacrosanct; unquestionable evidence that fairies did, indeed, walk among us. So intrigued by the images was he that he very nearly cancelled a lecture tour in Australia to visit with the family and interview Elsie and Frances himself. However, he was in need of a sudden influx of cold hard cash, so, off the great Down-Under he went. In his stead, he sent Garderner to interview the girls on his behalf. He also had the photographs sent to the American camera company, Kodak, and their British counterparts, Ilford. At Kodak, several technicians examined the photographs and, like Snelling, came to the conclusion that the photographs had not been faked, and what was seen in them did, indeed, exist… but they weren’t convinced they were images of fairies. Experts at Ilford, however, stated that they believed there was “some evidence of faking”.

In spite of these less than enthusiastic endorsements from Kodak and Snelling, as well as Ilford’s outright statement that the photographs were faked, Gardener and Doyle chose to view the two luke-warm testimony of the former parties as proof that two out of three experts had maybe, kinda, sorta not said it was total bullshit. And, as it was once so eloquently and beautifully stated -

And if that rule was good enough for the inimitable Meatloaf, it was good enough for Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. After all, it’s true - there ain’t no Coupé de ville hidin’ at the bottom of your Crackerjack box3.

Doyle also sent the photos esteemed physicist Sir Oliver Lodge; a pioneer in the field of radio who seems to be one of the many men who believed they should have the honor of being named the inventor of the radio rather than Guglielmo Marconi, and a devout and avowed Spiritualist. Like Doyle, Lodge, too, had lost a son to the violence on the Continent, and immersed himself in occultism in hopes of finding a way to contact him. However, while Doyle was quite bullish on the authenticity of the Wright girls’ photographs, Lodge was not so smitten. He suggested that the images of dancing pixies were doctored images of dancers superimposed upon the photograph of Frances, citing the distinctly Parisienne hairstyles of the fairies in question as the main tell that they were fraudulent. To be fair, that’s actually a rather astute and accurate assessment - as well as possibly the funniest piece of evidence for fakery one might point to. Doyle, however, was not moved by the argument that the fairies look like suspiciously fashionable French ladies.

Along with Gardener, Doyle sent a letter personally addressed to Elsie and Arthur, in which he asked for permission to print the photos in his article on fairies for The Strand Magazine.

Arthur, bewildered by the fact that his daughter’s prank had spiraled so far out of control that now the fucking Sherlock Holmes guy4 was reaching out to him, consented with what I imagine was a, Sure, man. Whatever. He also denied Doyle’s proposed payment for his permission, stating that if they were found to be genuine, he didn’t believe they should be soiled by money. Given that I’m fairly certain he still didn’t believe there was any possibility they were genuine, he was probably just trying to be done with the stupid hoax after two years of dealing with it.

Elsie and Frances’ reaction, on the other hand… I think it must have gone one of two ways.

Exhibit A)

AAAAAH! WE GOT THAT MOTHER FUCKER WHO WRITES SHERLOCK HOLMES! HOLY SHIT, WE ARE GOOD!

Exhibit B)

Uh… who wants what with us now?

Again, I must stress this is my own personal interpretation of events that is based solely on my own biases and reading of the events, but I lean more towards Exhibit B in how the girls must have reacted upon learning a household name in England and one of the preeminent figures in English literature not just wanted to speak with them, but whole-heartedly believed that they had truly taken photographs of fairies.

Because, the thing is, whatever the girl’s intentions were - or perhaps the family at large - what had started as what I believe to be a harmless prank had evolved into a fully-fledged national phenomenon across the British isles. Now that the photos had worked their way into the hands of a major public figure, the girls were left with two options - they could admit to the hoax, or they could commit to the bit.

Given the fact that we’re talking about this story over a full century later, I don’t need to tell you which tack they chose to take.

Now, by the time Gardener traveled to Cottingley, the year was 1920. Frances had moved to the town of Scarborough with her mother and her father, who managed to come back from France in one piece. As part of the investigation, the Wright family invited her to stay with them over the summer of that year, along with Gardener. Gardener noted that Arthur Wright was so sure that his daughter was, again, taking the piss that, shortly after the photographs had been taken, he had searched Elsie’s room while she out of the house, certain that he would find the cardboard cut-outs used in the photo or some other evidence of chicanery. He admitted that, despite his best efforts, he found nothing.

Gardener, in a book he later wrote about the events called Fairies: A Book of Real Fairies - which might just be the worst name for a book I’ve ever heard of before - said the following:

This being England, the weather that summer was not conducive to photography, especially in an age when cameras were much more fickle and temperamental to use than those we have installed literally everywhere today. It wouldn’t be until the 19th of August that the stereotypical English gloom would break, and the girls could set up their cameras5. Gardener, naturally, wanted to see how the metaphorical fairy-photo sausage was made, but the girls insisted that he could not come with them to photograph the fairies - they were a shy bunch, the fair folk, and they would only appear before trusted individuals, of which Gardener was not one.

Conveniently - perhaps a bit conspicuously - once the girls were left alone, they provided several glass plates bearing images of their exploits. Of these, two had images of fairies. Here’s one, depicting an older Frances marveling at a pixie who appears to be in the middle of an interpretive dance routine.

Here’s the other, showing good ol’ piss-takin’ Elsie being offered a flower by a pixie bearing a suspiciously modern bob-cut.

Two days later, they’d return to the beck and bring back one more photo - the last supposed evidence of the fair folk inhabiting Cottingley Beck.

Upon the photographs development, Gardener was floored. So eager was he to share this information with Doyle that he’d pay an exorbitant sum to telegraph the famous author the good news while he was in Melbourne, Australia. Doyle, in turn, spent a chunk of change to send the following reply.

Note the bit about a seance - that should really tell you how deep into the occult pool Doyle was, at the time.

Come December of 1920, when Doyle’s contracted obligation to provide The Strand Magazine with a non-fiction piece pertaining to fairies was filled, the photographs of Elsie, Frances, and their fairy friends would be included. In the article, out of consideration for the girls and their much beleaguered families - especially Arthur - Frances was referred to as Alice, Elsie was called Iris, and the Wright’s surname was changed to Carpenter.

What was supposed to be a sober assessment of fairies in traditional English folklore had been supplanted by a tale of the fairy folk gallivanting alongside two ordinary English girls in a no-name British village, furnished with all the dubious testimonies that Doyle had managed to collect from Snelling, Gardener, and other photograph experts that had never actually confirmed whether or not the pictures were of fairies or not. In the closing paragraphs of the article, Doyle wrote thusly:

Within days, the Christmas issue of The Strand Magazine had sold out across England, and the photographs of the Cottingley Fairies had broken escape-velocity. For the first time, they were shown to the British public at large.

Many accounts of the Cottingley Fairies debacle I found state that the public was immediately and unquestioningly convinced that the photographs were indisputable proof that the fae do, indeed, walk among us. Which, they do, but that’s neither here nor there. One such account from Irish author Henry De Vere Stacpoole, who, like fellow Irish author Sheridan Le Fanu of Carmilla fame, does not have a very Irish name, personally wrote to Doyle to say the following:

Many variations of this story paint the British public in much the same way - gullible idiots, if we’re being frank.

Actual contemporary responses to Doyle’s article suggest otherwise.

Novelist, essayist, and poet Maurice Hewlett wrote the following jab in response to Doyle’s essay in the literary journal, John O’ London’s Weekly:

In the London newspaper Truth, a contributor expressed the following sentiment:

Another man, Major John Hall-Edwards - himself an amateur photographer and one of the men responsible for developing the X-ray, if you can believe it - wrote the following scathing rebuke:

While the public imagination was certainly captured by the photographs, and some were convinced of their authenticity, the general consensus surrounding them seemed to be along the lines of, interesting, fun, but probably not real.

Gardener and Doyle, however, remained steadfast in their convictions. In 1922, Doyle would write a book on the affair titled, The Coming of the Fairies, in which he doubled down on his belief that Elsie and Frances had both photographed and interacted with fairies. Again, the publication was met with a lukewarm reception, and by this point, many prominent English thinkers and luminaries were of the opinion that poor Doyle, in his old age, was losing his marbles.

Gardener, in turn, paid one last visit to Cottingley in 1921, returning with more cameras, equipment, and this time accompanied by a man named Geoffrey Hodson. Hodson, it seems, was a rather eccentric character; not only was he one of the leading figures of the English branch of the Theosophical Society, like Gardener, but he also claimed to be in contact with a high-ranking angel who revealed unto him many secrets of the cosmos, and wrote extensively on the topic.

This time, the girls failed to photograph any fairies. In fact, they claimed that the fairies ghosted them outright and didn’t show up at all. It appeared that the fairies were as bored with them as they were with the fairies. Hodson, however, claimed otherwise - upon visiting the beck, he reported that the place was lousy with fairies. He spent hours there, feverishly filling notebooks with his encounters with the fae of Cottingley Beck. I’m not sure where Elsie and Frances were at this time, but, again, in the screenplay that’s developing in my head, I can picture the two of them watching Hodson sit by the creek-side, shooting side-eyed glances at one another as he hold one-sided conversations with unseen fae visitors.

They didn’t do anything to stop him. If anything, they enabled his delusions - whether he was insanely sincere or just putting them on for the bit is anyone’s guess, but given just how much he wrote about the topic of fairies, angels, and nature spirits, I can only assume it was the latter - and apparently played along with him.

By the time Gardener and Hodson’s visit was finished, I imagine that the girls were glad to see them go, and quite ready to wash their hands of the whole affair.

With no more photographs forthcoming and Doyle’s book on the subject being greeted with apathy and skepticism, public interest - and Elsie and Frances’ - in the fairies waned.

The two young women slipped out of the public eye, married, and moved abroad. It wouldn’t be until 1966 that the story would once again make headlines when a reporter would track down Elsie for an interview. While I can’t find the interview in full, apparently, Elsie was a little less bullish on the fairies being real; she copped to the fact that they might have been figments of her imagination… but that didn’t mean they weren’t real. She might have, she claimed, inadvertently found some way to photograph her own imaginary confabulations. You know - as one does.

The revelation of Iris Carpenter’s identity as Elsie Wright and the interview sparked renewed interest in the story that would thrust the cousins back into the national spotlight for the remainder of their lives.

In 1971, British news program Nationwide once again sought out Elsie for an interview. She stuck to her guns - not about the fairies, but her apparent ability to capture daydreams on cellulose, stating:

Both Elsie and Francis would sit down for a televised interview with Yorkshire Television. Again - footage of this is apparently difficult to find. Pertinently, though, both women backed off the fairy angle, with one of them going so far as to claim, a rational person doesn't see fairies. I’m sure that both Doyle and Gardener were rolling in their graves.

They did, however, deny that they had doctored the photographs.

And they were telling the truth about that. As Snelling had accurately surmised, what was seen in the picture was exactly what had been in front of the camera. It just wasn’t fairies.

In 1983, the ruse would finally come to an end. An article in the paranormal magazine, The Unexplained, would be published, detailing the how’s and why’s everyone had always wanted to know. Most importantly, it confirmed what most already suspected; it had all been one big joke.

Elsie would confirm that, once she heard Frances tell her mother she’d gone to see the fairies down by the beck, she was struck by inspiration. Originally, she intended for it to be nothing but a bit of light-hearted mischief at the expense of her father, who she hoped would be a little more receptive, or at least confused, by the photographs. She was disappointed that he so easily sussed out exactly how she’d done it, too - despite her protestations, the fairies in the photographs were, indeed, drawings Elsie had made that had been placed on cardboard, cut out, and stuck to the ground with hairpins, just as her father had surmised.

The reason Arthur never found anything incriminating in her room - his words, not mine - was because the girls disposed of the evidence in the woods after taking the first picture. The only reason there was even a second photograph at all was because, according to Frances’ daughter, Elsie got a little butt-hurt over all the attention Frances was getting for being the subject of the first photograph. So, shortly after, she invited Frances down to the beck, where Frances found her already set up to take a photograph with a cardboard cut-out of a gnome. Reportedly, Frances’ only comment was, What a hideous old man. I imagine that Elsie must have said something like, C’mon, man, you got to take your picture with the fairies, it’s only fair I get one, too.

Afterwords, Elsie made Frances swear to keep the hoax a secret.

Strangely, both of them did still say that there truly were fairies in the beck. And that they’d actually seen them. They just didn’t photograph them. Why? Who knows. Old habits die hard, I guess. One must respect their commitment to the bit.

The women would give further interviews throughout the early eighties, in which the two would offer conflicting information, particularly around the fifth and final photograph. While Elsie would maintain that it, like the others, were fake, Frances strangely insisted that it was the only among the lot that did depict true fae.

“It was a wet Saturday afternoon and we were just mooching about with our cameras and Elsie had nothing prepared. I saw these fairies building up in the grasses and just aimed the camera and took a photograph.”

Both women also claimed to be the one who took the final photo, though this could be chalked up to the faulty memory of an aging mind.

In 1985, in another interview with Yorkshire Television, Elsie and Frances would be asked why they continued to play along with the hoax as it spiraled beyond the confines of Cottingley and captured the imagination of the entire country. Simply put, once Doyle got involved, they felt as if they couldn’t tell the truth. In fact, they felt guilty that they had managed to involve a man like Doyle in what was supposed to be an innocuous prank. What would happen if they admitted it was all a hoax that one of England’s preeminent great men had fallen for? How would that make them look? How would that make him look?

Elsie said thusly:

"Two village kids and a brilliant man like Conan Doyle – well, we could only keep quiet."

Frances, in turn, added:

When the story of the Cottingley Fairies is retold, it’s often done in a way that I find completely demeans Arthur Conan Doyle. Now, Edward Gardener and Geoffrey Hodson - who I must add the girls thought was a fake from the word go and only played along with him out of mischief - they make easy targets to malign, what with their high-ranking positions in an occult, new age religious movements. But Doyle? One of Edwardian England’s preeminent literary figures? Shouldn’t he have known better? How was he duped by two bumpkin kids from the sticks with nothing but a few shitty pictures of cardboard cut-outs?

I think Frances’ statement is the answer - they wanted to be taken in.

In the aftermath of the first World War, the horrors experienced by so many English citizens both at home and on the front left the public wanting for feel-good stories that left a fuzzy, warm feeling in the chest. Many, like Doyle, truly wanted to believe there was something more magical, more spiritual, simply more than the crude world of material and matter. They wanted to believe there was another world where fantastical things could happen. It was something of a societal coping mechanism. A story about two young English girls being visited by fairies? That was exactly the kind of story that many people simply wanted to hear.

People wanted to believe in fairies. Why? Well, for the same reason I do - it makes the world just a bit more interesting.

This is all to say that I don’t think Elsie and Frances truly duped Doyle into believing their story; he convinced himself to believe the authenticity of a story he wanted to hear.

Just as Elsie and Frances feared, the revelation that their story had been a hoax did lead to disastrous consequences. Both women were harangued in the press and by the public, who attributed their decades-long charade to malice rather than the compassion for Doyle (and self-preservation for themselves) that they believed it to be. According to one woman - Jane Cooper - it was a scam.

And it ruined her father.

Joe Cooper was a Yorkshire man and sociology professor at Leeds University. He was also a war hero - Cooper was a decorated pilot who’d served in the RAF Bomber Command during the Second World War. His family would say he had nerves of steel.

Like Doyle, he had a strong fascination with the paranormal, of which he wrote about and investigated often. After a chance meeting with a friend of one of the Cottingley cousins at a bookstore, he took a keen interest in the story that his daughter described as an obsession. In 1975, dedicated himself to cataloguing their story when he took early retirement from his position to research nothing but the Cottingley Fairies. Cooper claimed that he invested many years and a small fortune into his studies. Around this time, Elsie and Frances were both in their seventies, living on opposite sides of England, and not on speaking terms. Both of them contributed to Cooper’s research. He’d present them with chapters of his book, and both of them would give him new details, request he change passages, correct some lines, redact others. In some cases, the information they provided was conflicting. Puzzled though he was, Cooper continued to work with them in good faith.

He’d drive between Nottingham - where Elsie lived - and Ramsgate - where Frances lived - and his own home in Bradford. For reference, Bradford is two hours by car north of Nottingham. Bradford is five hours north of Ramsgate. Needless to say, young Jane didn’t see much of her father during this time. You can probably extrapolate just how much time he spent on the road. He also spent a not-insignificant amount of time with the two women. He’d sit and talk with them for hours. He’d even take them out on the town and buy them lunch. According to some, he considered them friends.

For years, the two cousins continued to insist to Joe Cooper that their story was true. He continued to drive across the country on an almost daily basis to visit them and invest his time and dwindling finances into his research on them. Cooper put his personal life and professional career on hold, all for the purpose of investigating what they knew to be a hoax the entire time.

Then, in 1981, Frances finally broke. She divulged the truth to Joe Cooper in private. She even confided in him that she was surprised he ever took the story seriously at all. When he called Elsie, she confirmed what he already knew. Cooper later wrote, I felt my whole world shift.

Shirley Cooper - Joe’s then wife - said the following to The Daily Express:

In 1983, The Unexplained magazine expose about the Cottingley Fairies released, Joe Cooper was reportedly a broken man. His life’s work - his magnum opus - was dashed. Now, everyone else knew the sad truth that he’d wasted years and his own personal wealth chasing a literal fairy tale. Humiliated, he disappeared. Jane and Shirley Cooper claim that, one night, shortly after the interview was published, he simply left the house and didn’t return. Shirley stated thusly:

Joe was a very trusting, honest man and was made to look a fool. It was tragic.

Shirley called Frances Griffiths, hoping that she might find where her husband had disappeared to. Frances told her the following:

“I haven’t seen him since we both confessed to him that they were fakes.”6

She went so far as to claim that Elsie had been using Joe to maintain the fame and get the attention she always, apparently, so desperately craved. Once, she’d been the talk of a nation; now, she was a lonely old woman. Shirley, somehow, managed to get Elsie to meet with her in the aftermath of Joe’s disappearance. It was an awkward meeting she described thusly:

Joe Cooper would return to his family some years later, though, how long he was missing for, exactly, I can’t seem to find. By that point, however, the divorce papers had been filed. His family was gone. It was all over except the crying. Joe continued to work on a book about the Cottingley Fairies, titled The Case of the Cottingley Fairies, which he published in 1998. Even after it was adapted into a film called Fairy Tale: A True Story, he reportedly received no royalties from either book sales or movie tickets.

Jane, for her part, said the following:

Is this true? Frankly, I don’t know. I’ve found differing information. I am sympathetic to Jane’s plight, and as a fellow fan of the paranormal who desperately wants to believe, I certainly have my share of sympathy for her father, Joe. But I did find an article on his passing - published by The Guardian, which is not exactly a small or obscure publication - which seems to imply that he was still doing well for himself in his later years and was not the penniless broken man Jane seems to paint him as. In fact, in all the articles I can find about Joe Cooper, he seems to be something of an admired figure for his role as the man who exposed the lie.

As much as Joe Cooper is painted by his family as the victim of a cruel hoax by two old women manipulating him for money and attention - and I do think there is some truth to this - I also think that Elsie and Frances themselves were victims, in a way.

As I mentioned before, by the time Joe Cooper tracked the women down, they were not on speaking terms. The decades-long and ever-mounting pressure of the endless grift likely had some part to play in their falling out. Even once they did reestablish communication, the correspondences between them - published by Frances’ daughter, Christine Lynch, in her own book, Reflections on the Cottingley Fairies - were bitter and filled with resentment for one another. It seems as if each blamed the other for dragging them into the situation willingly. One such account from Frances states thusly:

I also purposefully omitted the fact that the article in which the cousins confessed to their fakery, published in The Unexplained magazine in 1983, was done so without their consent. It was not a sit down interview in which they came clean - it was an expose of information compiled from personal statements they had given to someone in confidence.

And it had been published by Joe Cooper.

Note how I never said that Elsie or Frances did an interview with The Unexplained. Note also how, after 1983, they did a lot of interviews with the press - kinda like damage control.

No doubt frustrated, enraged, and despondent that he had been lied to and strung along for almost a decade by the quarreling cousins, he chose to meet his betrayal with betrayal in kind, and expose the fraud for what it was. If you were wondering why, exactly, the public was so hostile to Elsie and Frances after their hoax was unveiled, this was why - the truth was uncovered without their consent, without their input, by a man who was wronged by them and let everyone know they wronged him. Of course they were going to look bad.

Obviously, Christine Lynch is quite sympathetic to her mother Frances’s side of the story, stating the following:

This leaves us with a conundrum - who was in the right? Who was in the wrong? Had Joe Cooper charmed and swindled a pair of sweet old ladies into confessing their decades long, harmless hoax for his own gain? Had Elsie and Frances manipulated Joe Cooper, stringing him along for their own benefit, resulting in the upending of his once ideal life?

Did Frances, when she finally admitted the truth to Joe, berate and belittle him? Oh, Joe - I can’t believe you actually took me seriously! How dense are you? Or was it a more soft let-down? Oh, Joe… I’m sorry, but I have to tell you - I never expected you to become this invested in the story.

Likewise, did Joe publish his article as a means of betraying the cousins with sinister intent, or did he simply do what he needed to do to wash his hands of over a decade of devoting his life to validating a hoax?

Personally, I think the truth, as it often does, lays somewhere in the middle. Both parties acted unwisely. Both parties had their reasons for doing what they did and acted in their own best interests. It’s also important to keep in mind that Christine Lynch is trying to sell her book - a hybrid of her mother’s memoirs, correspondences between Elsie and Frances, and her own thoughts on the matter - while Jane Cooper is attempting to sell the script for a television series about her father’s side of the story. Both of these parties are clearly trying to sell conflicting stories that, in many ways, are mutually exclusive. They have every reason to paint the other party as the unambiguous antagonists.

Frankly, there’s no real way of knowing who was in the right and who was in the wrong, or if there even is a clearly defined right or wrong side of the argument to be on. I’m not certain there is. At the end of the day, we have nothing but the second-hand testimony of Joe Cooper, Frances Griffiths, and Elsie Wright’s family to go on, and all of them have their own incentives for bias.

The tale of the Cottingley Fairies is one that has fascinated me endlessly since I learned of it. Now, I didn’t need to be told it was a hoax - honestly, the fact that the fairies are clearly illustrated dispelled any illusions that they might have been genuine fair folk, even when I was young. But it is a tale about how wildly a simple, harmless joke joke can spiral out of control, and, more importantly, how one lie often becomes two, and two becomes three, and, before you know it, you’ve constructed this elaborate web-work of falsehoods so complex that it becomes impossible to tell where one ends and another begins, or even where the fallacious meets reality.

For as much as I do think Joe Cooper was an unfortunate victim of the lies spun by the cousins, I also believe that the biggest victims of the story were those who told it to begin with; by the end of their lives, both Elsie and Frances were exhausted. They’d been exhausted with their simple, childish tale of fairies for a long, long time. They were trapped in a tale of their own creation and felt as if they were unable to speak to the truth. When they finally did, it cost them their public reputations, and it cost Joe Cooper much more. Yet, I can’t help but think that once it all came tumbling down around them, they didn’t feel some modicum of relief. After a almost a century of living this lie - they were free.

Unfortunately, they wouldn’t have terribly long to enjoy it. Cooper’s expose released in 1983. Frances died three years later in 1986. Elsie would follow in 1988. Joe Cooper himself would pass from a stroke in 2011, many years later.

Many have retold the story of the Cottingley Fairies. It’s one of the most famous hoaxes not just in the history of England, but perhaps in all of history, period. As I’ve explained throughout, the major actors are portrayed erroneously in most accounts I’ve found. Polly Wright, Arthur Conan Doyle, Joe Cooper, and the British public at large are painted as witless buffoons that whole-heartedly bought the photographs authenticity without a shred of incredulity, which simply isn’t the case. For one, by all accounts, the pictures were never seriously considered definitive proof of the existence of fairies by the majority of the British public. Though photography technology was relatively primitive at the time, people weren’t stupid - they knew hucksters could manipulate, doctor, and stage photographs, and it happened all the time.

Even those who did believe the story, like Doyle, were not the hoodwinked idiots duped by a pair of village girls they’re often portrayed to be. To present them in such a way is not just demeaning and degrading, but also fallacious and mean-spirited. These were intelligent but deeply wounded people, traumatized by a cataclysmic conflict, desperately looking for hope in a world in which it was in scarce supply. Likewise, the cousins themselves are often depicted as malicious, scheming, and money-hungry, when, really, I think that by the end, they were just two tired old women who were suffering from the knock-on effects of a white lie that had grown to monstrous proportions.

There have been many books and movies made adapting the tale. From what I’ve seen, most of them, in my opinion, take themselves far too seriously. They’re melodramatic. They’re schmaltzy. They often portray Elsie and Frances as a pair of innocent, albeit misguided girls, who didn’t have all that much sense to begin with. Again - that isn’t the case. The two girls were quite clever, even as children. But even the most clever and cunning of us can work ourselves into tight situations. In fact, I think clever people, who are often convinced they’re more intelligent and competent than they really are (note that I’m not calling them stupid, just overzealous), are usually the most liable to work themselves into a pickle like the one Elsie and Frances did.

In fact, I think there’s an incredible missed opportunity that this whole fiasco is always adapted into fiction and cinema as a sober soap opera or wistful tale of childish innocence misapplied rather the comedy-of-errors it truly is; I’d like to see a film in which an unwitting, staid, and quiet Frances is drawn into a hoax perpetuated by her older, more canny, attention-seeking cousin, and begrudgingly forced to continue the charade as each little lie they tell only compounds the consequences that might come with telling the truth. I can see the scene quite vividly in my head in which Arthur Wright confronts the girls with the letter from Doyle, which triggers a slow pan onto Frances’s wide-eyed, slack-jawed face as she realizes just how far beyond their control their little joke went, and how deep she is in the shit.

In 1917, Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths started a joke. Many think that the joke was on Arthur Conan Doyle, or Edward Gardener, or Joe Cooper, the English public, even the world as a whole. But neither of them could have ever known that day they photographed Frances with cardboard cut-outs of fairies traced from a children’s book that the joke, ultimately, was on them.

And, just as the song goes, the joke didn’t end until they finally died. Which started the whole world laughing.

At least by today’s standards.

This is also the same series where King Arthur and Mordred are depicted as women, Thomas Edison has the head of a white lion and wears a power suit, and Leonardo DaVinci is a twelve year old girl (with the mind of the actual DaVinci). The why to all of this is that the creator of the series is a sex pervert.

If you disagree that Two Out Of Three Ain’t Bad isn’t one of the premier love ballads of the 20th Century, I’ll be waiting for you behind the Denny’s at sundown. Come packing.

I really cannot stress this enough, but Doyle reaching out to them over these photos would be like Steven King emailing you asking if a video you posted of a person with a bed-sheet on their head was a real ghost.

As a personal aside, when I was in England this summer, the weather was quite lovely. It didn’t rain, not even once.

Keep in mind, Frances told Joe the truth in 1981. The publication was made in 1983. They hadn’t spoken between that time.

I had never heard this story, how fascinating and tragic. I think you nailed it with your comedy of errors comment. Thank you for this write up!

"They’d been exhausted with their simple, childish tale of fairies for a long, long time. They were trapped in a tale of their own creation and felt as if they were unable to speak to the truth."

Almost as though they were... tricked by the Fair Folk!

The photos have a compelling quality to them. I'm not sure how to describe it. There's some fusion of graininess and blurriness, and the inherent unreality of the fairies, that leads me to imagine what it might be like if I were to actually see some surreal shit like this.

Oh, and thanks for turning me on to the Cryptonauts podcast. That's become a comforting listen for me this past month or so.