Deconstructing the Curious Case of Chiaki J. Konaka

Otaku, Disney Adults, Lovecraft, a whole lot of Early Aughts Nostaglia, and the Phenomenon of Stuck Culture.

Remember how I said I’d have the second part to the Critical Drain coming up next?

Now, I didn’t mean to… but, unfortunately, that article is shaping up to be quite a hefty piece of work with a lot of research and links and all sorts of things, and, even though it’s mostly finished, I keep finding bits and pieces to tack on, and a whole lot of things that I feel as if need to be expounded upon that I just kinda glossed over in my first draft.

There’s other reasons, as well - other creative endeavors, cross-country travel, balancing social obligations, and keeping myself physically active and enjoying the last dregs of summer before I lose the ability to ride my bike for four or five months… it all keeps an ape very busy. Which is a good thing! Idle simian hands are the devil’s favorite playthings. But, at the same time, I haven’t been able to complete the second part of that series.

But, to keep the momentum going, I went into my drafts and dusted off this piece that’s been sitting on the shelf for quite a while. As I moved into more political and/or esoteric topics and strayed away from the cultural realm, I decided to put it on hold until I got into the mood to comment on culture again. It’s one of a handful of deep-dives into certain pieces of media that I’ve just been waiting for a moment to share.

Given the relatively niche subject and heavily indulgent nature of this piece, I know it probably won’t be to everyone’s taste. Though it was originally intended to be a simple observation about a piece of media I very much enjoyed as a child and its connection to the odious Disney Adults, it turned into a full-blown exploration into the creator behind it, the history of a popular shonen anime series, and the nature and egregious misuse of the deconstruction trope in fiction, and a brief look at the otaku phenomenon in Japan, and a whole lot of wandering down memory lane. It all ties together, I promise.

I invite you to give it a little sample, see how you like it, and, if it isn’t for you, well, there’s plenty of varied content coming down the pipeline soon. Regardless, I hope you enjoy yourself, and thank you all for the support; it means the world.

The urge to make the subtitle of this Turning Japanese was intense. Though I prevailed, the song is now firmly stuck in my head.

Now, you must suffer with me. This song would probably never even see a single radio play today, but damn does it, as the kids would say, slap.

I digress.

This one ended up being a little longer than I anticipated, but, I had a lot of fun writing it. It's as much a love letter to an underappreciated series and an eccentric writer as it is an indulgent Thompsonian gonzo thought exercise as it is an example of the phenomenon of taking a children's series and marketing it to adults. This one is a little different than cynical attempt by Disney to get Funko Americans to spend money at the expense of their ostensible target audience. Though I can’t say that the corporate culprits in this case were any less cynical in their ploy to bilk hard-earned money from consumers, the end result is something that is fondly remembered and held in high regard by the modest fandom around it, yet still offers us an interesting look at the phenomenon of stuck culture, the knock-on effects of a lopsided age pyramid, and how a man who had no business spearheading a show for children got the opportunity to anyways.

This is the Curious Case of Chiaki J. Konaka.

But, before I can tell you that story, first, I must tell you this story.

The year is 2005. I’m in in fifth grade. I think I’m morbidly obese. I don’t know why - I wasn’t - but it doesn’t matter what I am, because what one thinks usually supersedes reality. So, I take my little white ass out to the garage and run on to the sadly neglected treadmill that lives out there, in the spot where my dad should have parked his car, but never did. I didn’t know anything about fitness but I understood running burned calories, and if I burned calories, I would lose weight. I guess I was correct, in the broad strokes, but, now that I’m actively trying to lose weight, I could only wish it were so easy.

I digress again.

My parents had set up a small television set so, on the rare occasion they used the treadmill, they wouldn’t have to suffer without a distraction. This was a boon for me, because I could watch cartoons and run on the treadmill at the same time. So, I started this routine where I’d go and run until I made myself sick, then just stand there, draped over the support bars, soaked in sweat, and watch cartoons while chugging those little fun-size Gatorade bottles (all that artificial Red Dye 40 did something to my developing brain, I suspect).

My audio-visual drug of choice was Toon Disney. It was a channel where all the old cartoons in Disney’s back catalogue that were too old or too unfashionable for the teen chic Disney Channel could be dumped on. Duck Tales, Goof Troop, Darkwing Duck, Gargoyles, Winnie the Pooh Adventures (a term that could only be used very lightly, given I don’t remember the adventures of Pooh and company being very high adrenaline) - shows like that. I remember some show based on the gummy bears candy, too, but it only came on late at night, when I was already passing out despite my best attempts to persist, so I thought it was some sort of fabricated recollection or a hypnogogic hallucination I mistook for a memory until I found out a year or two ago that it was very much a real thing.

At the time, entertainment for children in America was still shaking from the impact of the Pokemon fad, which hit Western shores in 1998, but, like a faulty bomb, didn’t explode until 1999. In the aftermath, every television company was desperate to snap up more shonen anime, if not to do mortal combat with Pokemon in the ratings, then to hopefully catch the wave, collect some quick cash from the allowances and piggy banks of little boys and girls across the country, and ride the wake before it fizzled out. This scramble for Japanese IP’s was not unnoticed by Disney television execs, but, like Germany in the Great Game of Colonialism, they came late to the party, and all the choice cuts of both Africa and Anime had already been claimed by their adversaries.

Tragic.

So, they did what Disney still does best - they bought some smaller companies and threw their newly acquired assets on a new programming block. And, to keep the Imperial Germany metaphor full circle, yeah, there were some unclaimed scraps floating around they took as their own, too, but I just wanted to be funny with that comparison and now it’s getting long winded so forget it. Thus, the programming block Jetix was established on Toon Disney.

Jetix was, ostensibly, a block tailor made for the age cohort I belonged to - namely seven to thirteen year old boys - where Disney threw a bunch of programming that was either tangentially anime or sufficiently anime inspired, but any crap that looked like it might sell toys to a young male audience got added in over time.

This block aired around the time I would torture myself on the treadmill, and I watched a lot of it. Did I like most of it? No. But, by that time of night, Cartoon Network’s offerings interested me less, and Nickelodeon had already switched to showing reruns of 90’s sitcoms I was too young to care about, so, it was either Jetix, or Full House. And I was not about to suffer through Full House.

Now, Disney had acquired Fox Kids and ABC not long before this time, and with it, they’d acquired two heavy-hitting properties from Japan that will be pertinent to the discussion at hand - Saban's Power Rangers, which had a large and passionate built-in fanbase that persist unto this day, and another series called Digimon, both of which were broadcast on the Jetix block.

The story of Digimon is an intriguing one unto itself. The name would lead one to believe it was a quick, slapdash attempt to cobble together a Pokemon-esque property to catch some of the run-off from Nintendo's Pokemon success, but in actuality, Digimon was created as a spin-off of the Tamagotchi digital pet fad.

Bandai, the massive Japanese toy manufacturer, was seeing wild success with the Tamagotchi toys both domestically and abroad, and figured they could push even more units to young boys if they did the same thing, but instead of the digital pet inside your little plastic egg being a cutesy Hello Kitty knock-off, it was a sick dinosaur, because dinosaurs are awesome and Hello Kitty is dumb and lame and gay1. I’m sure there was some small degree of trying to catch some of the Pokemon hype for themselves, but I think the lop-sided rivalry between the two would only come once the Pokemon anime was released, and Bandai realized, Hey, we could probably make a couple bucks off an anime of our own, too.

As someone who was at ground zero of the initial impact site of the Pokemon phenomenon of ‘98, I can tell you that Digimon was widely regarded as the dollar store alternative to Pokemon by most kids. It was the Great Value to the name brand product. Acetaminophen to Tylenol. That weird cereal that came in bags with the bootleg, half-assed Tony the Tiger printed on a paper label to your box of General Mills High Fructose Corn-Syrup Crunchies Frosted Flakes.

In contrast to Pokemon, which ran the gamut from cute mouse critters to floating magnets and ambulatory piles of sludge and demon bugs with knives for hands, Digimon designs were always a bit more… weird. They often had really pronounced veins, big eyes that made them look cracked-out and unhinged, and various elements like random pieces of armor or bandages and, like, bullet holes in their bodies that made them look a whole lot less cuddly and fun than the average Pokemon, and more like something that would bite your hand off if you tried to pet it.

Did I watch Digimon? Oh, yes - I watched it. I remember one morning we were late to church because I was too enthralled with the antics of the digital monsters to put on my Sunday Best, which did not make my parents happy. But did I watch it like I watched Pokemon? Oh, no - no I did not. Most kids didn't. I woke up at five in the morning, before the sun was even up, every Saturday just to make sure that I didn’t miss the weekly new episode of Pokemon that broadcast on Kid’s WB. I wasn’t a Yu-Gi-Oh kid - that series never did much for me - but damn it if I didn’t sit through the new episodes of Yu-Gi-Oh and every other anime that Kid's WB acquired just to see what hijinks that dumbass Ash Ketchum and OP-Plz-Nerf Pikachu would get up to every week. I distinctly remember, one weekend, my dad being woken up by the noise from the television, since the family TV in the den was unambiguously my territory on Saturday mornings, and staggering out, bleary-eyed and barely functional, to find me sitting cross-legged in front of the TV with my bowl of Cinnamon Toast Crunch, enraptured by this:

He really should have spared me my eventual fate as a weeaboo and cut the infection out there and then, root and stem, by turning off the television and making me throw a football and run suicides at the local tennis court, but hindsight is 20/20, I suppose.

The salient point here is that I was a fiend for Pokemon, and like any junkie, I needed another comparable hit, so like a coke addict smoking crack rocks for a quick buzz, I naturally went to Digimon to get my fix of ten year olds having cool monsters commit violence on their behalf.

By the time Jetix became a thing, the fourth season of Digimon - Digimon Frontier - was currently airing, which was the season where the kids who ended up in the Digimon world could turn into Digimon, which, to be perfectly frank, was fucking awesome if you were eleven. It’s still kind of cool, because I’d love to be able to turn into a nine foot tall dragon guy and punch fuckers who drive ten under in the fast lane with fire gloves rather than work in an office.

But, more importantly, there were re-runs of the third season of Digimon airing as well. This season is what's pertinent to our discussion. This is the season known as Digimon Tamers.

You didn't come here for a review of a shonen anime from the mid-2000's. At least, I'm assuming you didn't. But, I will say this - Digimon Tamers was the high water mark for the entire “monster collecting” genre. Even though Pokemon was the much more commercially successful series, now being the most profitable IP in the entire world (yes, really), raking in even more billions than Michael Mouse (I shan’t call him Mickey, in good faith), Marvel, and Star Wars, the anime has never and probably will never even came close to sniffing the quality of any of the first four seasons of Digimon.

I suspect the fact that Digimon only had a middling fan following in Japan and an even more modest fanbase in the West might have been behind their motivation for turning out quality anime - they had to bring something to the table besides cool monsters to wrest eyeballs away from Pikachu - but that's beside the point. What's important is, out of every series airing on the Jetix, Digimon Frontier and Digimon Tamers were the two that I found myself engaged with like nothing else the block had to offer. Watching a bunch of young adult Kiwis pretending to be American high schoolers and faking the worst yankee accents you ever god damn heard on Power Rangers just didn’t cut the mustard for me.

If you'll allow me, let me give you some context and a brief synopsis of Digimon Tamers.

As I said, Tamers was the third season of the Digimon anime, but took a sharp turn in a markedly different direction from it’s predecessors. The first two seasons of Digimon were sequential - the second season was a direct sequel to the first, and some of the main characters from the first season were integral characters of the second, while the rest of the cast still bopped around in the background of the plot. It was a story that built on itself.

Tamers deviated from this, and re-started from the ground up. While the first two seasons of Digimon did get much darker than the Pokemon anime ever dared to, Tamers took it to a different level still

Tamers, in a very meta take on the genre, took place in what was nominally the “real” world, where Digimon was a successful and widely popular franchise2 where the characters, the card game, the franchise, were all well known to the ten year old protagonists, who were voracious little addicts of the franchise who just couldn’t get enough of it. Through what amounts to inexplicable techno-magic, those Digimon on their trading cards and in their video games - literal digital monsters from a parallel cyber-dimension - begin to bleed into the real world, and, naturally, the task of managing the trouble falls to clique of ten year olds - the eponymous Tamers - by pure circumstance. Because, you know, that’s how it happens.

Thrown into the mix is a shadowy and sinister government intelligence agency who seek to eliminate and/or control the ultra-dimensional interlopers, a group of graying, middle-aged computer programmers that “invented” the Digimon and their world in their college years and then slapped a brand on it to sell to children, and the children's respective friends and families, all of whom are gradually drawn into this rapidly escalating conflict as Digimon from the other world begin to manifest in reality with increasing frequency and severity, with the digital beasts in question graduating from “annoying pissant” to “devestating kaiju” in degrees of threat. The result is a tense, dark, mature, and very metatextual departure from the original two seasons as grade school children try and balance their normal fourth grade lives with curbing the incursions of dangerous, otherworldly monsters, hiding their activities from their increasingly concerned and confused families, avoiding sinister G-Men, and cope with their own deteriorating mental health, which ultimately culminates with a bizarre, Lovecraftian twist as some other malicious, alien force entirely begins to seep into their reality along with the Digimon, which ultimately threatens to unravel the very fabric of existence of both worlds.

Now, I would be doing the first two seasons a disservice to say that some of these themes were not touched on in them, or that they were bad. For a series made to sell toys and video games, the first two seasons of Digimon are actually quite good themselves.

For one, the first season was concluded with a very enjoyable movie directed by the talented Mamoru Hosada called Our War Game, the story of which would later serve as the blueprint for his stellar feature film, Summer Wars, which can both be summed up as, “Remember that dogshit book Ready Player One? Yeah, this is that concept, but done well.”

Secondly, in the first two seasons of Digimon, there are plenty of horrible monsters breaching the gap between the Digimon world and “reality” to wreak havoc in Tokyo, and the families of the children are very involved in the story once it shifts from the monster world to Japan. And it doesn’t shy away from showing these parents as being imperfect - one girl lives with a hyper-protective, overly-controlling single mother, a pair of brothers are separated and used as pawns in their parents bitter divorce, one is adopted and struggles with the resulting identity issues; you weren’t getting that kind of material in Pokemon. There's even notes of the bizarre and Lovecraftian in the very briefly mentioned and regrettably not expounded upon “Dark Ocean” in Season 2, where an outside force beyond both reality and the Digimon world exerts a pernicious and manipulative influence upon protagonists and villains alike.

I also never recall the stakes of Pokemon being raised to ‘nuclear annihilation’ like they did two or three times over the course of Digimon, and by the time the series concluded, the action had escalated to knock-down, drag-out kaiju fights between children and their digimon companions in locales ranging from New York to Moscow to Mexico City, which, frankly, was fucking awesome.

All the elements that made Tamers great were present in seasons one and two of Digimon. But, ultimately, for as mature as some of the themes presented in them were, the tone was mostly breezy and comedic, and, by and large, it didn’t take itself too seriously. Even though you had a skull-headed demon Digimon threatening to pop off nukes across the world, he was still shouting shit like, I GOTTA BONE TO PICK WITH YOU! while hacking into the Pentagon.

Tamers, however, took all of what made the first seasons, and ratcheted it up to eleven. It got dark. It got weird. The kids in seasons one and two were put in hairy situations, but never got to stressed out about it for long. In Tamers, the kids were having nervous meltdowns because their parents were accusing them of sneaking off to do illicit activities; they do what they have to do to save the world, and their reward is having their mother in tears and their father losing all trust in them.

We’ve all been there, right?

Anyways, I once attended a Q&A panel at an anime convention with some of the creative staff that worked on Digimon Seasons 1 and 2. They explained that they intended to take the story of those seasons further, and they big ideas, too, but by 2002, it was clear that the arms race between themselves and the Pokemon anime was over; Pokemon had come out as the undisputed champ, and had enough money to buy to buy the country of Uzbekistan to prove it.

For reference, both Digimon and Pokemon had movies release in American theatres circa 2000. The Digimon movie - which was actually three very good individual movies butchered into one messy, slapped together product, grossed $16 million at the box office.

Pokemon - which had the audacity to add the subtitle, The First Movie, by the way - how did it fare?

Oh.

Is as so often the tragic reality, the better product was trounced by the one with superior marketing and boatloads of money.3 But Bandai was not ready to throw in the towel. They were going to try again, but they weren’t going to give the staff from Season 1 and 2 another opportunity to fail. They were out. New blood was coming in. They were going to reinvent the series. They were going to rebuild it from the ground up.

They were gonna get weird with it.

Enter one Chiaki J. Konaka.

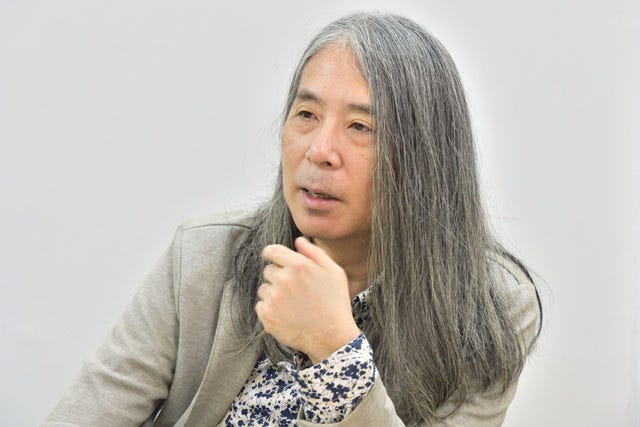

You can probably tell right away that Mr. Konaka is an odd duck. You'd be right. For instance, the J in his name was his true middle initial - John - as he was born to a Japanese Catholic family. Only that wasn’t true, and in 2015 he copped to the fact that he just added John to his name because he thought it looked cool. I respect that.

The man has quite an illustrious career as both a novelist and screenplay writer. Now, a lot of his most notable work all seems to have been done around the same time, which was shortly before and after Tamers (the guy had one hell of a 2003), but to understand what a bizarre choice this man was to tap for the job of penning a new season of Digimon, here are some choice cuts from his career:

A whole lot of Lovecraft mythos short stories. Can’t get enough of the big writhing, screeching, tentacled madness, this guy. He’s classified as a Lovecraft Mythos Author, and everything he’s ever touched has notes of our favorite attic-dwelling, neurotic, viciously racist New England shut-in author (and no, I’m not talking about Steven King).

The Big O - which is commonly described as Batman if he had a giant robot instead of a suit, though it’s better described as a mind-bending sci-fi Film Noir detective story mixed with the Kaiju genre with the undertones of a psychological thriller and existential horror. It’s as good as it sounds.

Hellsing, which is about Dracula being paid by Abraham van Helsing’s granddaughter to help eliminate paranormal threats in England for the Anglican church, which eventually results in a nearly apocalyptic conflict with a lost Nazi regiment with S.S. werewolves and a legion of zombies that destroy London (if only we could be so lucky). Very bloody. Very gory. Lots of fun. Again, it’s as good as it sounds.4

Princess Tutu. Funny name, I know, but the plot is… well, it’s difficult to describe succinctly. Let’s just say if you took Sailor Moon, the Brothers Grimm, the popular ballets of the late 1800’s like Swan Lake and the Nutcracker, put them in a blender and hit puree, slather the result in meta-textual commentary in which self-aware characters fight the author of their own story, kick it up a notch with a little existential horror, you’d have Princess Tutu. And yes - it is as good as it sounds

And - oh? What’s this little footnote in his credentials?

Oh… that explains… a lot about that whole Lovecraft-esque Dark Ocean subplot.

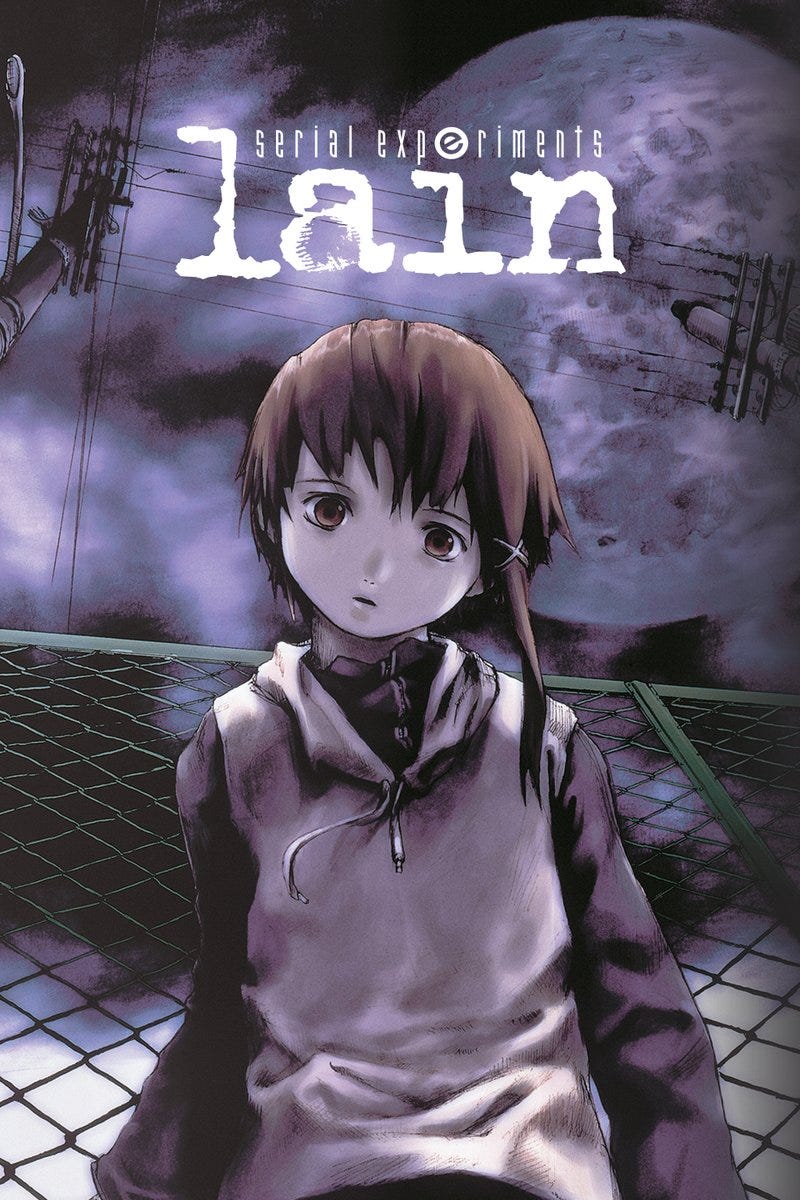

But, most notable of all Konaka’s works, his most well-regarded - or, at least, his most well-known - is 1998’s Serial Experiment’s Lain.

I’m not even going to try and explain this one. I couldn’t, even if I wanted to. I’ll tell you that it is a surrealist cyberpunk nightmare steeped in paranoia and disturbing imagery that is intensely weird, intensely creepy, and even though it’s not always clear what the series is trying to say, you know it’s trying to say something.5 And a lot of what it is trying to say is about the internet, which was still a largely novelty in 1998, and in the series it begins to infect reality like a virulent fungus, spreading madness and insanity in its wake - in the business, we like to call that prophetic.

The lines between reality, dreams, and cyberspace - never all that well defined to begin with - begin to blur. People go crazy. People die. Then they come back through the internet. Or do they?

It’s quite literally impossible to say.

To put it simply, Serial Experiments Lain is an animated head-trip for the digital age. I’d recommend watching it like I did - alone, late at night, with the lights off, hunched in front of the antiquated fossil of a computer we had in our upstairs rumpus room, on some sketchy streaming site, all in one sitting. It really brings you into series, as I truly felt like I was getting into the headspace of the protagonist, Lain; a paranoid, anti-social little freak sitting in a dark room staring at a computer screen for mind-melting stretches of time, gradually losing her tenuous grip on sanity and reality as the internet rots her brain in real time.

There’s even this scene where, inexplicably, some grey alien in a Freddy Krueger sweater opens her door while she’s sleeping and just stares at her. The doors to the game room had glass in them that looked out into the yawning, lightless black of the dark hallway, in which I was absolutely fucking certain I’d see that little asshole in his striped sweater leering back at me from just beyond the periphery of the computer monitor’s cold glow.

In the series, Lain gradually loses herself not in but to the internet and, by the end, there’s a very real question of not who she is, but what she is, which was very fitting because by the time I finished binging the series I certainly felt like something other than human, myself.

All jokes aside, though, Serial Experiments Lain is considered a landmark anime series. It is frequently cited as one of the best and most influential anime ever made, and almost always considered a must watch of the medium if you have any interest in it outside of bog-standard, surface level shonen schlock that most Western fans are content to call “DA GREATEST OF ALL TIME”.

I cannot overstate the popularity and critical acclaim that this series had in the early-2000’s anime scene. Lain herself was a ubiquitous sight across anime discussion forums - especially on 4chan in its younger years. If I have to tell you why the average anime fan using 4chan in 2005 would identify with a emotionally maladapated and socially retarded internet addict - what are you even doing here?

Now, let’s review our notes, shall we? Having briefly touched on Mr. Konaka’s contributions to anime, what all can we say he has a fondness for? What are the hallmarks of a Konaka story? What’s his forte, huh?

Cosmic and Existential Horror

Blood, gore, violence, scary monsters, and disturbing imagery

Horror, horror, horror, and more horror

A post-modern penchant for metatextual commentary

Paranoia, insanity, and the dissolution of the barriers between reality, dreams, and other worlds

Now, with all this in mind, we arrive at the question I’ve been asking myself ever since I first saw Digimon Tamers - who the fuck thought it was a good idea to let this guy pen a script for a kid’s cartoon?

Because I hope they got a promotion.

The end result, if you couldn’t tell, is something I enjoy quite a bit.

But, objectively speaking, I think most of us would agree that a man of Mr. Konaka’s particular tastes and talents would not be the first person we would call up to make a show for children. I mean, they were competing against the Pokemon anime, for the love of God, not William Gibson or George R.R. Martin.

In Digimon Tamers, the protagonist was running himself ragged trying to hide his dinosaur monster from another world because the military was trying to find it so they could dissect it and study it. In Pokemon, Ash was just being harassed by a pair of flamboyant homosexuals and their cat because they wanted to turn in his perfectly legal pet for a promotion at work.

If I can’t comprehend a horrible entity from beyond space-time that defies all description as an adult, I imagine little Timmy and Tammy are going to fare much better. Was this really the man they wanted? The target demographic for Digimon was still learning how to spell their own names!

Or were they?

Spoilers: they weren't.

Digimon Tamers was not made to appeal to the core demographic of elementary schoolers that were snapping up Pokemon merchandise before it even touched the shelf. Whether or not Bandai ever meant to beef with Nintendo over dominance in the Monster Collecting Series that Ends in -Mon field, or they got inadvertantly pulled into one while trying to sell dinosaur Tamagotchis, I can’t say, and it doesn’t matter - they did, and they lost. Pokemon had taken their cake, ate it, set fire to the bakery, and danced in the ashes. Bandai, stewing in bitter defeat, watching all the seven year olds feverishly dance in mindless and blind worship around Nintendo’s throne made from bricks of Yen in Pikachu t-shirts, knew damn well that the little yellow rodent held a vice-like grip on their prepubescent minds that no Digimon was going to break, no matter how sick their dinosaurs were.

So, you lost a battle. Oops.

It happens.

What do you do, then? Short of waving a dish towel in surrender, you find a new avenue of attack - preferably somewhere your enemy is ignoring, where there presence is weak and easy to overwhelm.

So, they knew they weren't going to break Nintendo's siren spell over the children… so what if they went after another audience?

Kids are fickle creatures. I remember when Pokemon was cool as hell, and I was a baller, a real shot caller back then, because I really did catch ‘em all and I had the mad playground cred to prove it. And then, 2003 rolls around. Pokemon: Ruby and Sapphire come out. I am all about it. I come to school, I got my Gameboy Advance - the transparent, crystal purple one, where you can see all the electronic guts inside - just swagged out head to toe in my light-up sketchers and Pokemon backpack. I'm ready to be the coolest kid in third grade, when the news is delivered to me like a .38 special right between the eyes at point blank;

“Dude… Pokemon is lame.”

They should have just shot me. It would have been less painful.

Basically overnight, by seemingly unanimous decision, some unnamed, faceless cabal of third graders, the tastemakers who divined what and what wasn't cool, had declared Pokemon lame.

Worse still - it could even be gay.

And this was back in the day when no one wanted to be gay.

Yu-Gi-Oh, though? Oh, now that… that was cool. That was awesome. That was even radical, according to a few early adopters.

I couldn't believe it. It was like a switch had been flipped without my consent or even my awareness. One day, I knew it all. The next, I knew nothing. I was a stranger in my own school. Adrift. Confused. Scared. And, apparently, not cool, and possibly gay, stumbling through the inverted social scene of my elementary school like the blinded and exiled Oedipus… if Oedipus had been wearing a shirt with Charizard on it and light-up tennis shoes.

This was but the first of many times a violent, sudden polarity shift in the fabric of culture would leave me speechless and stunned. First it was Pokemon. Now, I’m still lame because I refuse to download Tiktok and commit the name and bust sizes of every nineteen year old goth e-girl to memory.

Grandpa Simpson said it best.

Well, after that, I was never too concerned about being cool again. I knew I’d never keep up, and, really, I didn’t want to - if I did, I’d know not just who Ice Spice is (which I learned against my will), but I’d also know her music, which apparently she makes. Or so I’m told. I’m also nothing if not loyal - that’s why I stuck with Pokemon through thick and thin and have played all the mainline games to this day, regardless of how cool it is or isn’t (and survived to see it’s massive cultural resurgence in recent years, so, ipso facto, I became kind of cool again). It’s also why I stuck with girlfriends for so long even though they were cratering harder that the Galactic Starcruiser, but, hey - loyalty is a virtue in scarce supply, these days.

I say all of this just to illustrate the caprice of children. We know it well. If you have a young child now and they like Bluey? Expect to find their beloved Bluey plush they can't sleep without drawn and quartered within a year. Two tops.

Yes, Pokemon had cornered the younger demographic, but there was a whole lot of pre-teens and older that were already convinced that Pikachu and friends were lame kiddie shit that they were too cool to debase themselves with. How many children had gotten in on the ground floor for the Pokemon craze, only to abandon it once their younger sibling decided they were going to rock up to the party in a Charizard t-shirt? How many middle schoolers saw the elementary school kids babbling about Pikachu and wanted nothing to do with it?

Just like Bandai created the entire Digimon franchise as an alternative for young boys in their digital pet scheme, they must have figured they could re-tool it as a more mature alternative to Pokemon. I suppose in a way, it always had been the thinking nine year old’s monster collecting anime of choice. But Bandai wasn’t just going for an anime with some more substance than Pokemon’s paper thin monster of the week formula. No - this wasn’t your snot-nosed little brother’s monster collecting anime. This was Digimon, bro.

Your little rodent can only say it's own name? Oh, that's cute. Well, my Digimon can talk and recite James Joyce verbatim.

What was that? Charizard could kill any Digimon ever?

Tch. Sure, kid. Y'know what? You got have fun watching your lame lizard smack around some dumb turtle that pukes bubbles. Us real men have better things to do. Oh, you mean you didn’t hear?

Our monsters have boobs.

So, you go get your gym badges, or whatever. We’re gonna make our buxom angel chicks have a slap fight. On a trampoline. Covered in oil.

Now, I’m being largely hyperbolic. The lovely angel lady above was one of the original monsters in the Digimon line-up, so it isn't as if they ratcheted up the fan service to attract the eyes of hormonal thirteen year olds in later seasons out of desperation. They did add Renamon in Tamers, but I choose to believe they had no idea what kind of depravity they were unleashing upon the world with her.

Even more importantly than the young teen demographic, Bandai doubtlessly had their eyes on another lucrative subset of consumers - and these, I suspect, were the most integral to their plans, as well as the most pertinent to the discussion of a stuck culture. This group, if you haven’t already guessed, are none other than the adult otaku.

Now, I specify adult otaku because the term otaku itself is a broad one. Anime fans in the West have long since used the word as a badge of honor, and named various conventions, products, and what have you after the word, while in it’s native Japanese, otaku was and still, at times, is used as a pejorative.

Not to say calling someone an otaku is the equivalent of using a racial slur, or that Japanese anime fans don’t proudly label themselves as otaku, but there aren’t any small children praying to God to make them the perfect otaku one day, not in Japan or in the States.

In the advent of Pokemon’s debut in the West, there was a thriving yet very small, very tight-knit, and very niche community of anime fans in the States that relied on trading bootleg VHS tapes with crude fan translated subtitles or primitive dubs that were edited in by very dedicated fans, often shipping tapes across the country, given how few and far between avid anime fans were at the time. The internet helped disseminate the medium more, but given the limited reach of the internet even into the late 90's, it was still very much a thing that only your friend’s weird brother in college liked to the public at large. Things were beginning to change come 2003, but it would take a few more years before more widespread internet access allowed the anime fandom to come into its own in the West and become the juggernaut we see today.

Such was not the case overseas. Given that Japanese anime fans didn’t have the language barrier to overcome, and could watch these series as they aired, the otaku scene in Japan was, as one would expect, already well-developed, and I really shouldn’t have to tell you that these people spent a lot of money on the hobby, even back then. Rampant, blind consumerism was almost a necessity to be an otaku. Even today, if you don’t have every piece of merchandise with your waifu’s face on it, ranging from acrylic statues to scraps of fabric, I ask you - do you really love her?

No. You don't. Simple as.

Now, that kind of consumerist behavior deserves it’s own deep dive one day, but suffice to say that if you wanted to push merchandise in the anime industry, these were the guys you wanted to court. Though the perception of the otaku has changed dramatically over the years - especially in the West, where anime has bizarrely become something of a fashionable subculture…

…back in the day, it was a pretty safe bet that if you identified as an otaku, you were single. There was probably a good chance you'd never even seen what was in between a girl’s legs before. Not with your own two eyes, at least. Many otaku worked lucrative jobs in Japan’s many burgeoning white collar industries, and even those who worked less well-compensated jobs were often living with their parents, which left them with an excess of income and not much to spend it on. I have to assume if any of them had kids, it was a negligible amount.

Put those traits together, and what do you have?

Childless, flush with money, often single, obsessed with some sort of mass media, which in turn becomes a foundation upon which they build an entire identity…

Huh. Why, that sounds an awful lot like those SINKs (Single Income, No Kids) fellas we talk about so much, doesn’t it?

Now, I wonder… why would Bandai take a well-establish franchise that lost their core demographic to a competitor and hire an illustrious and popular writer who made one of the most critically-acclaimed and well-known anime released in recent memory - a man who is basically royalty in the industry by this point - and have him overhaul your series as he sees fit in a way that appeals to a much older, much more mature audience, retrofitting it with all the tropes that made his previous works so successful with a different demographic with no children and an untapped motherlode of wealth they’re eager to spend?

Here’s the thing: Japan’s birthrate started cratering long before America’s did. Though there will always be a market for children’s entertainment, it will not always be as lucrative as other markets. There’s a reason that legacy tokusatsu series such as Kamen Rider, while still being ostensibly for children, is increasingly growing a wider adult fanbase both in Japan and the West and hiring writers like the infamous Gen Urobuchie - infamously known in the anime industry by the well-desereved nickname Urobutcher - to pen new seasons of the show.

A similar phenomenon has happened with the long-running magical girl franchise, Pretty Cure, which, again, is ostensibly for young girls, but continues to garner significant fan attention from adults. Most of them men.

Yeah, look, don’t think about it too hard, okay? It’s not worth it.

Of course, companies like Toei and Bandai know that adults with expendable money are where the big bucks are for merch sales, but, the other thing is, as people have less kids, adults are an increasingly important demographic for them to court, because it’s not just where more money is - it’s the only game in town.

Let’s go back to Disney. Same thing. People say go woke, go broke, yet, as they bleed money hand over fist, with many of their more recent movies underperforming if not outright bombing, they continue to double down on appealing to left-leaning, childless adults. Why?

Well, as kids make up a less and less significant portion of the market, and families with kids - who very often skew away from the left - gravitate away from Disney, who else does Disney have left to turn to?

This may sound silly - especially seeing the caliber of people Disney is trying to appeal to - but, honestly? I don’t fault them. These people - these Disney “adults”, to use the latter term lightly - they’re… not well, to put it simply. They’re vulnerable people. They’re the end product of modernity and neo-liberal society; people with no race. No country. No real religion. No real convictions or coherent political ideology, really, though they’ll protest to the opposite. Very often times, they have no family, outside of a long-term partner. Friends? Not many, usually.

These people are blank slates, looking for something to attach themselves to. A movement. A people. A tribe. A foundation to build an identity upon. And in a country where Mickey Mouse is more recognizable than Jesus, at this point?

Bob Iger’s got a ready-made identity for you, loaded and ready to roll. Just put the mouse ears, sing the songs, buy the tickets to the movies, and you’re part of the club - no questions asked.

It took a long time to get here, but this is it - this is what all the stories I told, recollections I… recollected, and all the context was about; basically so I could tell you that Bandai did to Digimon what Disney is doing today, but to everything in their catalogue.

But wait, you might say. YakubianApe, you devilishly handsome rogue, you’ve done nothing but shower Digimon Tamers with praise, while you spit curses most vile upon the name of Disney! Is it not hypocritical to admonish one and not the other?

To which I answer, emphatically, no.

And this is an explanation that I will give in two parts.

For one, there is nothing inherently wrong with shifting demographics. Look at the Harry Potter franchise - the books are often praised for gradually growing darker in tone and more mature in their themes as the narrative progresses. It’s often said they matured along with the children who first read The Sorcerer’s Stone when they were still in grade school. That’s not necessarily a problem, and for as critical as I can be of J.K. Rowling, if she did anything right with those books, advancing the maturity of the thematic framework as the timeline of the books progressed and the characters grew older would be it.

There are ways that you can re-imagine a work or a franchise for a new audience, whether it be younger and older, so long as you do it well, with tact, grace, skill, and talent.

Chiaki J. Konaka was actually the perfect man to do this for the Digimon series.

The term deconstruction - and commit that word to your memory now, as we will be coming back to it - is often used to describe Digimon Tamers. Tamers, some would say, is a deconstruction of the seasons that preceded it.

What is a deconstruction? It’s somewhat difficult to quantify. It’s often thrown around by people who fancy themselves intellectual critics who use the term to describe any piece of media that has any degree of genre awareness or even the slightest hint of meta-commentary, which is a very liberal and extremely generous use of it. Not long ago, I saw someone describe the abysmal She-Hulk series from the rapidly sinking S.S. Marvel Cinematic Universe as a deconstruction, as well as Wandavision and even Falcon and the Winter Soldier.6

So, let’s consult the experts. And by experts, I mean TV Tropes, because,despite it’s (well-deserved) reputation of being a hot-bed of some of the most depraved freaks to ever slink through the tubes of the internet, they are nothing if not thorough, and I find their definition of deconstruction to be both accurate and succinct.

"Deconstruction" literally means "to take something apart". When applied to tropes or other aspects of fiction, deconstruction means to take apart a trope in a way that exposes its inherent contradictions, often by exploring the difference between how the trope appears in this one work and how it compares to other relevant tropes or ideas both in fiction and Real Life. The simplest and most common method of applying Deconstruction to tropes in fiction among general audiences and fan bases, and the method most relevant to TV Tropes, takes the form of questioning "How would this trope play out with Real Life consequences applied to it?" or "What would cause this trope to appear in Real Life?"

Mr. Konaka does a masterful job of doing just this in Digimon Tamers.

Just to name one example that I’ve mentioned before; the idea of having a Digimon in the real world. As a kid, if you suddenly had a orange lizard that could spit fireballs and turn into a big-ass dinosaur, or a cat that could turn into a foxy angel lady7, your first reaction would be, hell yeah, this is the best thing to happen to me ever! while a radical ska-punk song plays in your head and you imagine all the cool things you’re gonna do with your dinosaur or angel lady. At the tender age of ten or eleven, I’d have chosen the dinosaur over the angel lady as my digital partner, but if I got stuck with her, the most depraved, debauched thing I’d have her do for me at that age is pretend to be my mom to get me out of school early. But I digress.

In the first season of Digimon, the protagonists have their Digimon come back to Japan with them about two-thirds through the series run. They try to hide them from their parents, but when they run off, the adults just roll their eyes and yell after them, You be back before bed time, alright? Later, when the parents meet the Digimon, there’s no screaming, no shouting, no Oh my God what the fuck is that thing?, they just kind of go, Haha, okay, that’s weird but alright, nice to meet you, weird monster creature.

In Tamers, the protagonist is ten years old. He’s not as slick as he likes to think he is. His parents know he’s sneaking out at night. Of course, the audience is aware he’s got a sick-ass dinosaur he’s trying to hide from the Men in Black, and he’s also stave off incursions by destructive and dangerous Digimon. His parents, obviously, do not know this, all they know is their son is leaving in the middle of the night, staying out late, despondent, constantly tired, skipping school, coming home with cuts and bruises, and every time they ask about what he’s doing, he deflects the question.

What do you think any decent parent would do in that situation?

Yeah, suddenly, that sick-ass dinosaur isn't so sick-ass anymore. In fact, he's kind of burden. He's big, he's bulky, he eats a lot, and now your parents think you're, like, doing drugs or committing crime because you're trying to keep this dumbass reptile from getting poached by the feds. Hell, you are having to steal food from the convenience store down the street just to keep his fat ass fed, because all that food ain’t cheap and you’re ten and your parents only give you pocket change.

At least with the angel chick, she could reasonably blend in to society a bit easier, but I imagine you'd have a very uncomfortable conversations with your parents about why you, as a ten year old, are suddenly hanging out all the time with a busty blonde woman at least twice your age. Sure would suck to go to school and then come home to see your Digimon being frog-marched out of your house in cuffs and thrown in the back of a squad car.

Point is, a good deconstruction takes a genre, isolates all the things that make you say, “Hell yeah, that would rock!” and reframe them in a way that makes you say, “Oh shit, actually having this dinosaur sucks.”

It's not always negative, either. Sometimes, it will just take a trope and ask question. Investigate it. Explore it. For example, it would ask you, “Okay, well, that's cool you have a dinosaur, but what are you gonna feed it?”

Uh oh. Didn't think about that. Opens up a whole litany of possibilities, both good and bad. Deconstructions get a bad rap these days - I can think of one we've already discussed that poisoned the well for a lot of people - but a good, carefully made deconstruction, crafted by someone who knows what they're doing, doesn't actually deconstruct anything - it builds upon it. It takes what you love and critically examines it, really makes you think about it, challenges you, asks you, “Why do you like this?”

And the best of them leave you thinking, “That's why!”

Because a good, proper deconstruction will tear apart whatever genre it's, well, deconstructing, it will turn over every rock, shine a light on every shadow, ask some uncomfortable questions, tear down the idols and icons, but always build it back up, so when the dust clears, and the room falls silent, you realize, that's why you like it.

That’s why it was good to begin with. It has flaws. It had problems. Everything does.

But it isn't bad.

And that's why Digimon Tamers is a successful deconstruction. Konaka did the impossible and made the prospect of having a giant dinosaur friend look like a pain in the ass to a ten year old. But, he also reaffirmed why, despite being a pain in the ass, having a dinosaur friend would be worth all the trouble. Would having my own personal sentient dinosaur pal to ride into glorious battle atop be a burden? Yes. But it would be a burden well worth bearing.

It reminds me of how my boomer acquaintances talk about women. Listen, son - chicks? Ain’t nothin’ but trouble. But, as I always say, the problems that come with having a good woman in your life are better than the problems that come with not having one.

Nothing in life that’s easy is worth doing - whether it be trying to keep the Men in Black from slicing up your interdimensional dinosaur friend like deli meat or finding your wife an anniversary gift she’ll actually like.

Now, let’s tie this back to the bane of pop culture.

The Last Jedi was an attempt at a deconstruction. And not a successful one. It didn't rebuild anything. It only destroyed. It only tore down. It disassembled the iconography of the original trilogy and pissed all over it it. Rian John has admitted to not being a big Star Wars fan. In fact, he's said less than flattering things about the series. You don't need to hear him say it - you can tell just from the way he handles The Last Jedi that he has little respect for the original movies.

And that's fine. But, I ask you - why would you hire that man to write and direct a Star Wars movie, then?

Mr. Konaka was probably not an avid Digimon fan before he came onto write Tamers. Maybe he got the job and looked at it and said, “God, what a load of shit.” I doubt it, but, really, who knows. But, he is, if nothing else, a professional, and he was paid to do a job, and he did it well. Whatever biases he might have had against the series, he didn't let them bleed through, and he had some modicum of respect for the source material.

And this was a kids show.

Take this and apply it to Rian Johnson - what does it say about him as not just a creator, but a professional and a person that he was granted the keys to what was undeniably one of, if not the most revered and respected and beloved pieces of media in American culture, and, like an irreverent disrespectful teen with access to their uncle’s luxury sports cars, he crashed it and totaled it. Then, he had the nerve to get salty about it when people were mad at him over wrecking their favorite movie series.

A few words come to mind to describe Mr. Johnson. Narcissistic. Petty. Stupid. Just to name a few.

To successfully deconstruct a genre or a series, you truly have to understand it. To understand it, you really do have to have an affection, or at least, have a healthy respect for it.

Consider the following quote from the great Mel Brooks:

This is why I believe Konaka had to have at least some respect for the Digimon franchise from the get go - he was able to find a great story within the silly premise of ten year olds with monster friends saving the world. Rian Johnson, conversely, saw Star Wars as a silly movie about space wizards for dorks and kids, and all he was able to pull out of it was a silly movie about space wizards for smug, insufferable losers.

Speaking strictly in terms of artistic integrity (and enjoyment), as much as a shonen anime and a movie about space wizards can have it, Chiaki J. Konaka succeeded where Rian Johnson failed. They both set out with the same intentions - to deconstruct the source material they had been given - and only one managed to do it well.

But, I've said it before, and I'll say it again - at least Rian Johnson tried. Not well, but he did.

J.J. Abrams never even tried to add any substance to his Star Wars movies; it was nothing but sugary, sickeningly sweet, cloying memberberry sludge.

I was going to compare Abrams and Konaka with the metaphor of a castle, where one built upon a foundation of stone and the other upon a foundation of sand, but I believe that, at this point, I’d be belaboring the point.

Now, this article - if you can believe it - was intended to be much, much longer, and dive more into the interesting Post-Tamer history of Digimon that, to my immense surprise, does an even better job at illustrating the Stuck Culture phenomenon than Tamers. Of course, I’d like to talk about other examples of Stuck Culture in Japan - I already hinted at taking a look at the infamous Gen Urobuchi, who’s another man who should have been kept far, far away from any media intended for children. But, Mr. Urobuchi will have to wait his turn in line.

But, to conclude, let’s finish on what became of Mr. Konaka.

Sadly, while Digimon Tamers was fairly successful both critically and among fans, it didn’t move quite enough merchandise to move the needle back in Bandai’s direction.

Was Mr. Konaka satisfied with his contribution to the series and walked away of his own accord? Or, was he shown the door, just as the showrunners before him? The season’s final episode does end on a note that leaves the door open for a potential follow-up. The Tamers cast did get two movies of their own that were both released following the conclusion of the season, but both stories take place during the events that transpired during the show’s run rather than after, and Mr. Konaka was not involved with either. Given that no series he’s been any significant part of has ever had a follow-up (or, if they did, he was uninvolved), I’m led to believe that the man is simply not one for sequels. Ultimately, Bandai moved in another direction once again and moved on to the aforementioned Digimon Frontier.

As for Mr. Konaka himself, despite having quite a prolific career both before and shortly after Tamers, he seems to have stepped away from the anime industry around 2007, with his last credits being the writer for the psychedelic and characteristically bizarre Mononoke and some other horror series I’ve never heard of. Even then, 2005 seems to be around the time he started to slow down precipitously. I’ve read a few sources and interviews that state he mostly sticks to penning novels and short stories these days, though information on his literary career in English is tragically scarce. Apparently, he teased a return to screenwriting in 2016, though this announcement was just that - a tease. One last yank of the chain for the road, I suppose.

I’d like to say that’s the end of his story, especially where it’s pertinent to the matter at hand. But, there’s one last tidbit that is… well, if you’ve stuck around this long, let’s just say this is something of a reward for your dedication.

When I said that the story of Tamers wasn’t continued past the conclusion of the animated program, and that Mr. Konaka had nothing to do with any further development on it… well, that wasn’t entirely true.

Now, the story of the Tamers cast effectively ends with the second and final movie, but, in some small, very strange, mostly irrelevant way, Mr. Konaka did continue the plot. Information on the following is, again, a bit scarce in English, but Mr. Konaka did write an Audio Drama that was released as a CD in 2003, and another in 2018, that followed the characters on into their later teenage years. Then, in 2021, Konaka attended DigiFes - a yearly fan event held in Japan - to celebrate the twentieth anniversary of Tamers’ release. The fans were in for a real treat - not only had Mr. Konaka written a follow-up to the Audio Drama from 2018, but it was going to be read, live, by the original voice cast from the anime. I’m sure those in attendance were waiting with breathless anticipation.

And… well, there’s really not anything I could say that would be any more hilarious than what actually happened.

And, with that, there’s really only one thing left to say:

If you made it this far, I sincerely thank you for taking this wild ride down memory lane with me. I hope you enjoyed, and, as always, I hope you return to the lakeside for another dive into the dark waters of our culture.

I’d like to apologize to Ms. Kitty and, more importantly, Sanrio’s legal department, and clarify these statements were not made with the intention to offend her but strictly for the sake of comedy.

So you know it had to be fiction.

Though, the Pokemon games were better, and that ultimately was what gave them the edge, I think.

Has a killer soundtrack, too.

Maybe a little too much.

I didn’t watch She-Hulk, but from what I saw, I can assure you, it is not a deconstruction of anything so much as it is a very shallow and very self-unaware quote-unquote parody that doesn’t even seem to know what it’s trying to spoof.

Yeah, the buxom angel chick is the second stage evolution of a cat. You learn to go with it.

Loved this. Was just talking about Digimon the other day and tried to explain how wild and dark it was compared to Pokemon.

I remember Lain, vaguely - my own brain was getting eaten by the Internet at the time. Weren't there Knights Templar in night vision goggles or some shit?

"Before Ryan Gosling became literally me in Drive and Blade Runner 2049"

Any chance you could do a piece on Blade Runner 2049? That one hit at precisely the right time for me. It seemed like a perfect snapshot of my inner life in 2017.