I know you know what Pokemon is.

Even if you’ve never played a single one of the dozens of games, watched a single one of the 1,269 of episodes (or one of the twenty-three movies) of the animated series, or engaged with the franchise in any meaningful way at all, I know that you are still at least aware that it exists. When Pikachu and his1 150 original pals struck the American continent in 1997… well, it actually took a few years for them to pick up steam, but by the time the century turned, you quite literally could not escape Pokemon. If, by some chance, you did manage to skate by untouched, the last surviving remnants of the blissfully ignorant were all but exterminated down to the last when the release of Niantic’s virtual reality mobile game, Pokemon Go, released in 2016, resulting in a renaissance of global cultural relevancy that has yet to entirely fade. Even the card game, which was late-arriving tertiary addition to the anime and video game upon the series debut, experienced such a resurgence in popularity over the past several years that people are still regularly busted for stealing large quantities of them from both stores and shipping trucks - sometimes at gunpoint.

Personally, I find Pokemon to be one of the most fascinating pieces of media to ever come out of the land of the Rising Sun, if not in all of global media entirely. I’m not just saying that because I was squarely in the franchise’s target demographic when it first invaded American shores, and still bear the scars to show it to this day (i.e. I still regularly play the new installments of the mainline games, as disappointing as they may be). Even viewed from a completely objective stand-point, it is a total anomaly. The Empire that Pikachu Built, in a world that makes sense, would have never become the pop culture behemoth it became. There’s a good argument to be made that it should have never been a success at all.

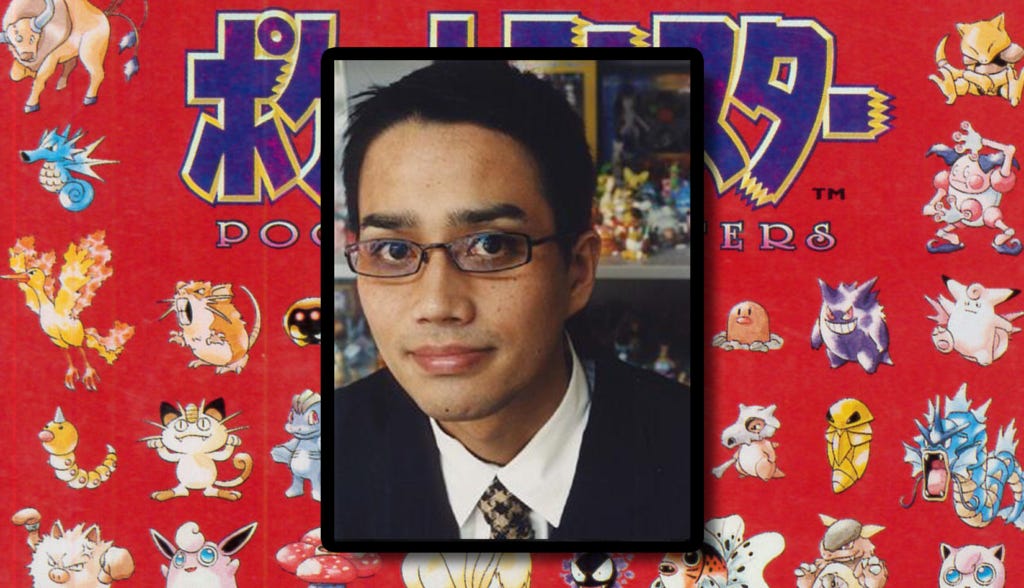

I will, in some vague and distant future, make a full critical examination of the game’s long and unconventional development cycle. What you need to know now is that the game was originally a passion project cooked up by one Satoshi Tajiri.

In the late 80’s, Tajiri founded a small game development team under the name Game Freak; a name that referenced a series of hand-drawn, amateur video game magazines he would create during his youth, as well as his own certified addiction to the games of an electronic persuasion. Much of the original staff consisted of high school friends who figured that it would be something fun to do on the side as they navigated early adulthood and found their way in life.

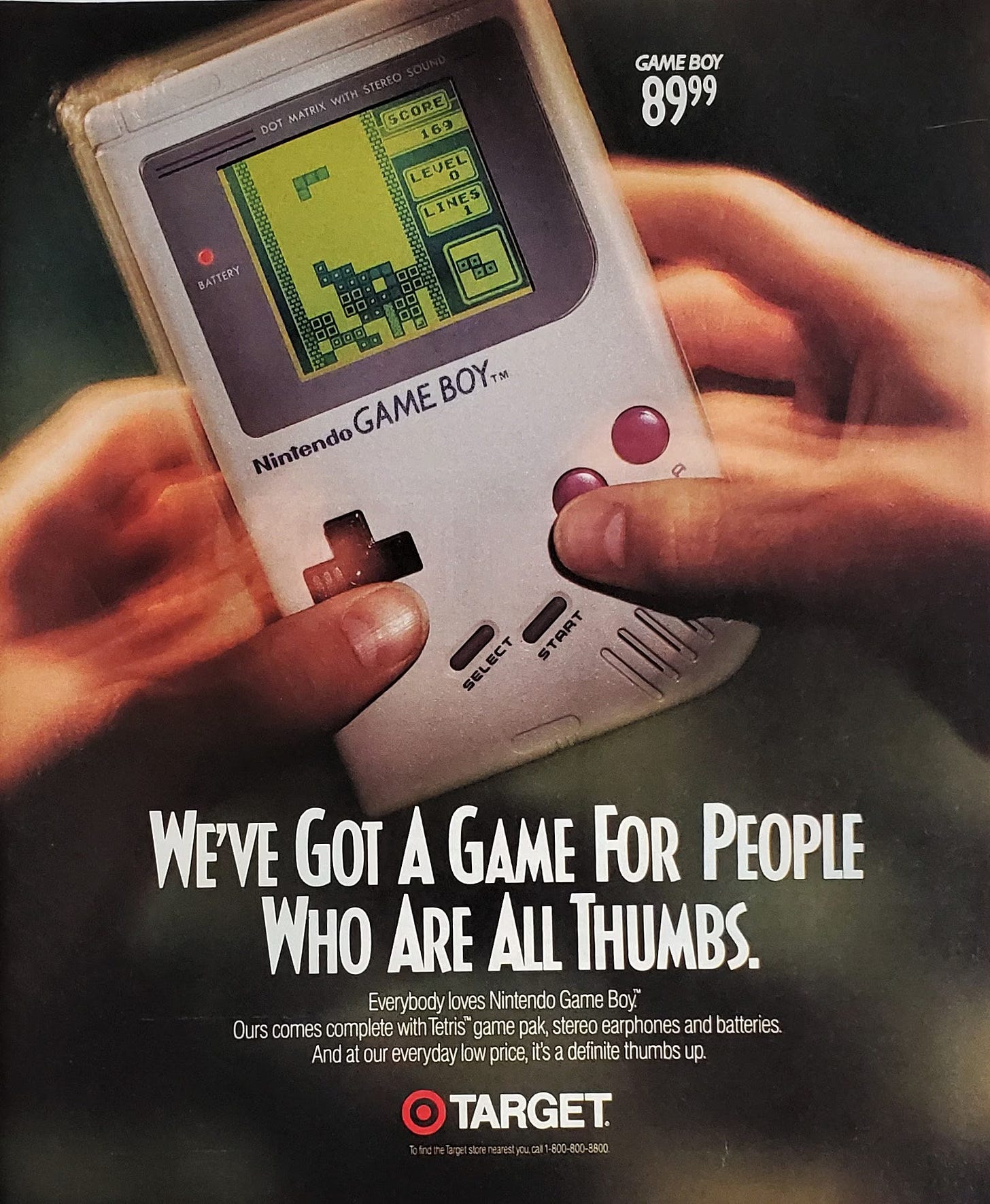

After developing some modest and minor successes for Nintendo, and cajoling some friends he’d made in the company’s higher ranks, the video game titan was willing to humor his pitch for a project he called Pocket Monsters. However, with only a small team and a shoe-string budget to work with, the game’s development would drag on for a gruelingly long period of time. Chronic and consistent software and programming issues would only exacerbate their problems. Simply put, Tajiri’s vision for the project was ambitious and far beyond the scope of what the relative amateurs were capable of producing. By the time what would ultimately become Pokemon: Red Version and Pokemon: Green Version were ready for release, over half-a-decade had elapsed, and the original Gameboy the two games were poised to debut on had gone from exciting, cutting-edge technology to old hat. The system was at the end of its lifestyle. Nintendo’s hopes for the games’ success were just shy of nil. They had wasted enough money on the development - they didn’t see the need to waste any more cash on marketing what they believed would be a dead-on-arrival game for a system that they thought no one was interested in playing anymore. One can only imagine that, by the time the games quietly limped onto store shelves, the Game Freak team was as exhausted as they were dejected.

However, what nobody within Game Freak or Nintendo seemed to anticipate was that the Gameboy, though nearing the end of its life cycle, was increasingly popular with school children. As the technology aged and the device came down in price, more and more second-hand units were finding their way into the hands of younger and younger players.

Combined with one last ditch marketing push in the popular CoroCoro Comic featuring a lottery in which twenty entrants would win access to the enigmatic 151st Pokemon, which was normally inaccessible in the game, the pin of the phenomenon grenade had been pulled.

Pokemon: Red Version and Pokemon: Green Version were released on February 27th, 1996 in Japan. By September of that year, a million copies of the games would be sold. By the end of 1997, a further seven million would be added to the count, with the number only increasing exponentially year over year until the sequels would arrive in 1999. Until 2022, the original line-up of Pokemon games were the best-selling video game titles in Japanese history.

Nearly thirty years later, with an estimated value of 98.8 billion dollars2, Pokemon is currently the single most profitable intellectual property in the world.

Not bad for a simple fella with a dream, eh?

For his part, Tajiri stepped away from the active development and took on a role of executive producer for all things Pokemon-related. At fifty-nine years old, he still holds this role today. Being something of a recluse, very little is known about the man’s personal life, but it can be safely assumed that he is happy, satisfied, and very, very wealthy.

Pretty incredible story, no? That’s the kind of underdog tale that the best kind of biopics are made of. Real aspirational stuff. I can easily see the final shot of the film, which freeze-frames on Tajiri leaping in mid-air as he prepares to Scrooge McDuck his way into a Pokeball-shaped swimming pool filled with Yen notes to the tune of We Are The Champions.

But, it’s also not really the story we’re here to discuss today. Like I said - one day, I’d really love to cover the deeply intriguing, often mysterious, and apparently tumultuous development cycle and origin of the games, but, for now… let’s rewind the clock back to 1997. Or, perhaps September of 1998, when the games first debuted in North America.

Back in those days, the internet was extant, and I can vouch with first-hand experiences that it was rife with a rich network of Pokemon fansites. But, as most of you are already aware, the internet was far from the ubiquitous presence it was today, and the usership but a fraction of what it would eventually swell to. If you wanted to look up a guide to uncover all the secrets the game was hiding, you could, but there was no guarantee that whatever fansite you were relying on for information was accurate. Again, I can vouch that most of them weren’t. The grand majority of them were far from comprehensive. You could, like me, also beg your parents to buy you an officially-sanctioned (and sometimes unofficially produced) game guide, but even those could be difficult to find depending on where you lived, and I distinctly recall them often being riddled with errors.

For the average kid, your resources when it came to navigating the sprawling little monster-infested 8-bit world in your Gameboy were limited. Especially when the game first launched. If you got the game or its first few sequels upon release, you were going into it blind. It was impossible to know what awaited you once you stuck in that thick, chunky cartridge with that satisfying analog click and booted up your game. In a lot of ways, it felt let genuinely embarking on an adventure - which is exactly the kind of experience Tajiri wanted to emulate, drawing upon his experiences exploring the Japanese countryside as a child and his disappointment as an adult as he watched the fields and forests he once ventured through gobbled up to make way for suburbs. In that sense, I think a lot of kids who grew up with the games owe Tajiri a debt of gratitude; for kids like me who were raised in sprawling, sterile suburbs that could only be traversed by car, in the era of stranger danger where our parents kept us on a short leash, Pokemon offered us an experience that we just weren’t going to get in real life. It gave us an adventure we could enjoy from the comfort of our own homes.

But that sense of adventure and mystery that came with not knowing what you were going to find when you first started up your Pokemon journey gave the world it was set in a vague sense of danger. Today, when a new game is released, the data is mined within hours of release, and every single aspect of the game is laid bare to be dissected, examined, quantified and catalogued. These days, the games usually leak before their official release date, and the entire thing is known inside and out before it even makes its way into the average player’s hands. No surprises. No mystery.

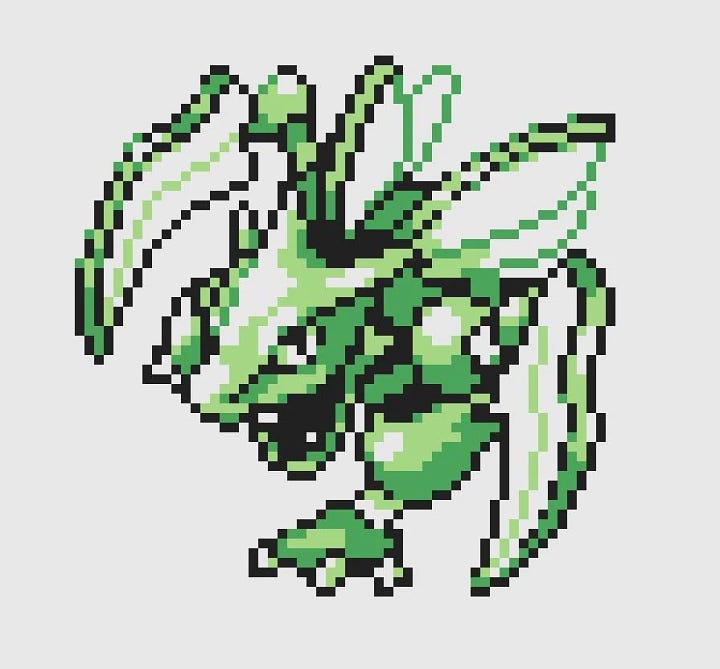

That was not the case with the original games. You didn’t know what you were getting into. You didn’t really know where you were going or what was waiting for you when you got there. The world of Pokemon was littered with caves, mountains, oceans, and dense, dark forests that were all crawling with all manner of beasties that ranged from cute and cuddly to possibly demonic. The crude sprite art of the original games did not help them look any more friendly.

But it was imperative that you did have to catch them all. Yep - you even gotta get the giant, sentient pile of toxic sludge that smells like death and can kill you with a touch and demon hell bug with giant blades for arms. Look, kid, the catchphrase is gotta catch ‘em all, not gotta catch some of ‘em or gotta catch the ones I like. Nut up or go home.

Just as the era of the data-mining would bring a close to the golden age of mystery and adventure in the Pokemon world, so too have recent installments to the mainline games have sanded off the rough edges the setting once had. I’ve been accused of waxing nostalgic when I say this, but the newer regions introduced in future games, as well as the people and Pokemon that populate it, feel much more sedate and sanitized than the originals.

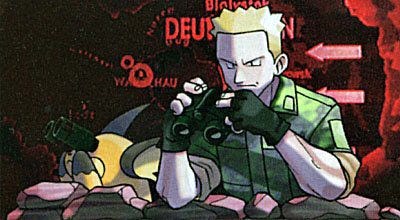

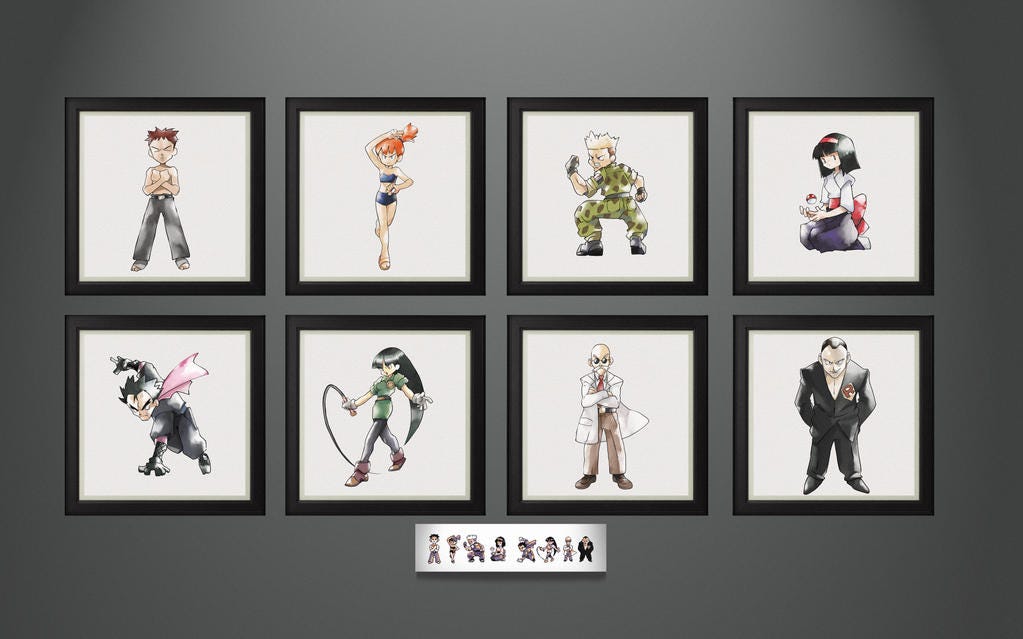

Again, here’s a quick compare and contrast between some of the gym leaders, which are often the most notable and important NPCs in the game.

Here’s the electric-type gym leader from Generation I. He’s a military guy. His name is literally Lieutenant Surge and his dialogue implies he’s seen some shit, man.

Here’s the electric-type gym leader from the latest installments of the game.

My problem isn’t that she’s a kawaii uguu anime gurrrl because, like, c’mon. It’s a game from Japan, all the female characters are gonna be like that. My beef with her is that she’s an online streamer-cum-social media influencer, and I just don’t like those type of people. She wasn’t even the first gym leader to be an insufferable social media e-celeb.

I’ll admit, I may be cherry picking here since there’s a coarse mix of based and cringe gym leaders in each generation, but the ratio has skewed hard to the cringe side of that equation in recent installments.

I would love to go into detail as to why the franchise has declined in quality over the years, but I also already tried during the first draft and it just came off as several paragraphs of Old Man Yells At Clouds about a game series most of you have probably never played and most likely don’t care about it.

I also don’t want to sound like too much of a Genwunner, which is community jargon for someone who is convinced that Gen I - or at least the early games in the series - are the best. It’s basically the Pokemon fandom’s equivalent of a racial slur. But, it must be said that anyone who’s being completely objective has to admit that the quality of the games has decreased since arguably hitting their peak during Gen V with Pokemon Black and White, circa 2010.

But real ones know Gen II with Pokemon: Gold and Silver were the best in the series. That’s not an objective measure. They’re just my favorite and, as we all know, my taste is immaculate and I’m right about everything.

But let’s rewind a bit. Return to what I said about the first generation being notably rougher around the edges than the later installments. And I don’t just mean that because the game was infamously buggy and the notoriously coded just to work at the bare minimum, and not much more. When I said the team was made of amateurs, I wasn’t kidding.

No - I mean that everything about the game had an edge to it. Compared to later games, which hold the player’s hand to the point that, at times, it feels as if it should play itself, the original games were unforgivingly hard, if not outright unfair at times. Part of this, it must be admitted, was just because the original crop of Pokemon were poorly balanced and there were some rather shoddy spots of programming that weren’t very well thought out, but, er… well, that’s not exactly an issue they’ve fixed over the past thirty years3.

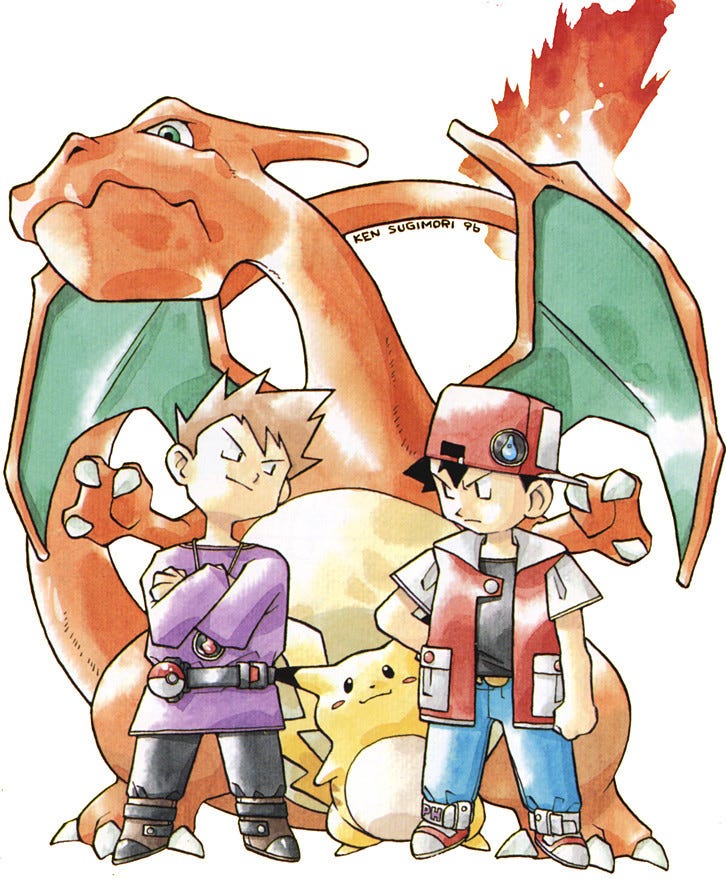

But, more importantly than the game’s difficulty, it’s the aesthetic that provides the game a layer of visual grit that only the X-TREEM 90’s could provide. Much of this comes from the art of chief art director and designer, Ken Sugimori.

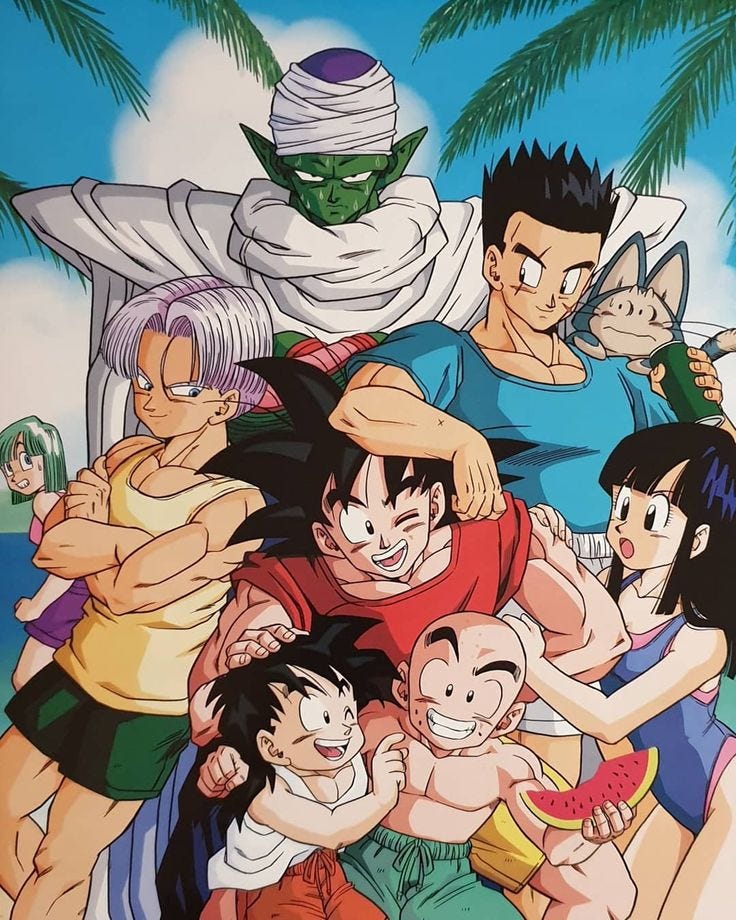

When it came to Sugimori’s art for the first two Pokemon games, he wore the inspiration he took from Akira Toriyama of Dragon Ball fame on his sleeve.

Even though the above image is not exactly representative of it, Sugimori took all the elements that Toriyama used to make Dragon Ball appealing to ten year old boys and applied them to Pokemon. The kids are weirdly short and their proportions are off. All the characters, regardless of age or gender, look like they’re prepared to hit you with the old tried and true, Heh… nothing personal, kid, always smirking and looking like they’re fully confident they’re going to beat your ass. Even the other kids.

For every cuddly, doe-eyed Pokemon like Jigglypuff or Vulpix, there’s a Rhyhorn or a Charizard or Mewtwo that looks like they’ll make a light hors d'oeuvre out of an unaccompanied minor. The region itself - dubbed Kanto after the real-life Kanto Plains of Japan on which it was loosely based - is comparatively hostile compared to later areas of the Pokemon world. Despite being modeled after one of the largest urban agglomerations on planet Earth, the cities are separated by long stretches of wilderness, populated by both wild Pokemon ready to maul you and hostile trainers looking to pad their win/loss ratio in a battle (and take your lunch money, while they’re at it). This is to say nothing of the criminal activity running rampant across the region, overseen by the enigmatic and corrupt final gym leader, who’s running the whole operation out of a shady casino. Even though this criminal syndicate was represented in the anime by a pair of flamboyant homosexuals and their pet cat, the entire joke was that they were the most incompetent members of the Pokemon world’s equivalent to the Yakuza.

The landscape of Kanto was dotted with remote and foreboding places where no one was coming to help you if things went pear-shaped. Far-flung islands with an interior network of sprawling, ice-choked caves. A derelict power plant sitting at the far corner of the map, rotting way as it was reclaimed by dangerous Pokemon. A burned-out chateau that served as the front for an illegal genetics laboratory, in which gestated a deranged, man-made abomination of immense power. Some of these places played host to literal Pokemon demi-gods4. All across the map, there were places that felt legitimately unsafe to tread through and fostered a sense of genuine mystery and danger, which is a feeling that the most recent installments, despite middling efforts, have failed to replicate.

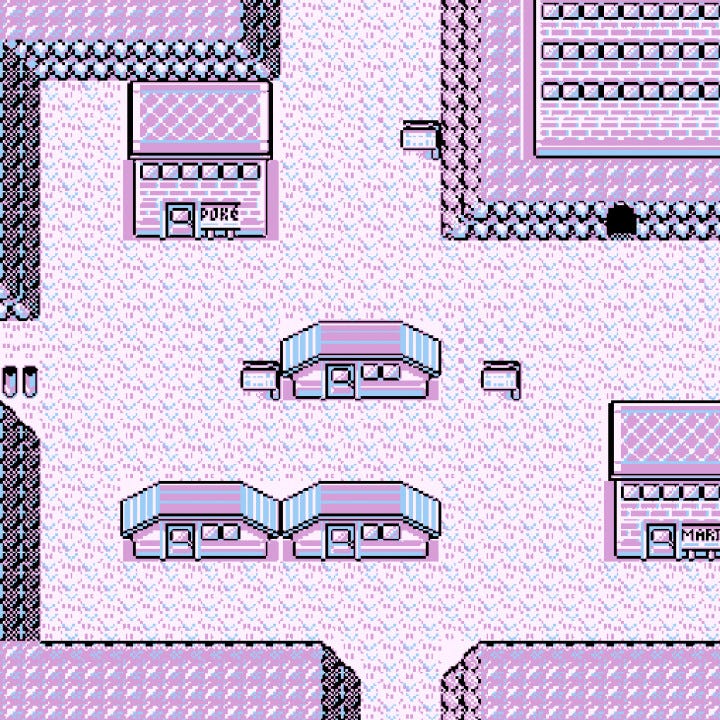

Among these dark and dangerous locales, perhaps none lodged itself in the memory of anyone who ever picked up a copy of the game more than Lavender Town. Situated at the far eastern corner of the map, not all too far from the abandoned power plant, Lavender Town is a small and easily over-looked corner of the Pokemon world. It’s notable as one of the few settlements in Kanto that lacks a gym. Compared to most of the other towns and cities you visit, it’s quite small. But what it lacks in population and relevance to the main plot, it more than makes up for by being creepy.

Lavender Town’s defining feature is the Pokemon Tower, seen in the top-right corner in the above image. Here, the player is introduced to a sad fact of reality in the Pokemon world - death is inescapable. The tower is a burial ground. A crypt. Yes; even Pokemon die. This shouldn’t be too surprising, as, along with taxes, death is the only certainty in this world and all others, but, when you’re a kid, you really don’t want to think about your adorable little Pikachu coming down with a terminal case of colon cancer. The tower is full of grieving trainers who will gladly tell you all about their dearly departed Pokemon pals as they mourn at their graves. Oh, and ghosts.

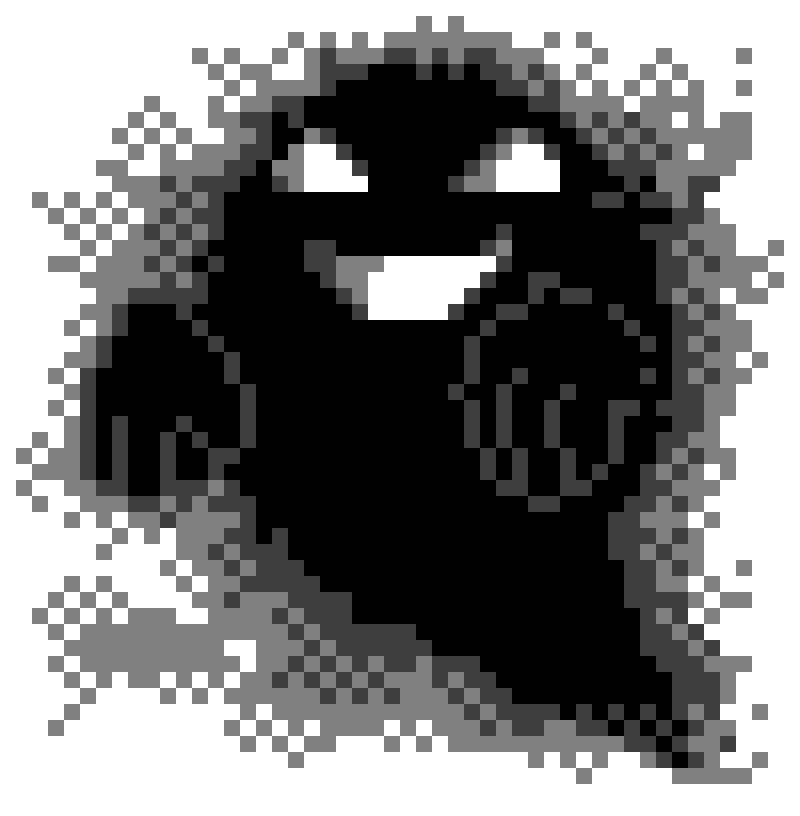

The place is fucking haunted. Again - not terribly surprising. When you first step into the tower, you can't proceed as you’re harangued by the spectral spirits of those gone before you, which appear as these nondescript ghost sprites that have forever burned themselves into the brains of all children who encountered them.

You couldn’t battle them. You couldn’t hurt them. You couldn’t catch them. All you could do was run.

Later in the game, once you receive a certain pair of ghost-busting goggles that let you see through these phantasms to reveal that these spooks aren’t the spirits of the dead, but rather illusions made by only three ghost-type Pokemon in the game.

Due to the games’ poor balancing, they were busted as fuck and everyone wanted them on their team. Also, it turned out that they weren’t mean or malicious - they were just your regular tricksters looking to scare little kids into wetting their pants. You know. For a goof. What makes ghost-type Pokemon different from spirits of the deceased? Don’t think too hard about it.

Why did people decide to create a giant, towering sky-scraper mausoleum in a po-dunk little town at the edge of the map to serve as a mega-crypt for any and all dead Pokemon? Again - don’t think too hard about it.

This is all to say that Lavender Town and the side-quest in the Pokemon Tower was a rather jarring and grim deviation from the norm. But what truly set Lavender Town apart from the other locales in the game - what really stuck in the head of all who passed through what I always imagined to be a dreary, fog-choked little town full of dingy, dilapidated homes - was the music.

The moment you stepped foot into Lavender Town, the upbeat music that underscored your travels up to that point is replaced by this unsettling, pitchy track that sounds like the auditory embodiment of paranoia.

I can’t say it’s scary per say, but it certainly isn’t pleasant. To rate it somewhere on the Fantano-scale, I’m feeling a strong eerie out of ten for this one.

Interestingly, in the direct sequel to Red and Blue, the song is revised to be a much more pleasant, albeit just as melancholic track.

Probably because the Pokemon Tower, during the gap in in-universe time between the two games, was renovated into a radio tower. Because where else would you put a radio tower besides a giant mausoleum filled with dead Pokemon in a small, out-of-the-way town? What’s the worst that could happen?

But there’s one more thing that Lavender Town is known for. And it has very little to do with the game.

In the early months of 1996, not long after the release of the original Pokemon games, Japan experienced an unprecedented rash of youth suicides. And I mean youth. Not teenagers5. It’s estimated that somewhere around two hundred grade-school children were victims of this trend. This disturbing phenomenon was accompanied by a more wide-spread outbreak of unusual behavior and illnesses among this young age cohort; reports tell of children reporting to the hospital suffering from debilitating migraines, severe nausea, and seizures. The incidents were not localized. Most of the afflicted children had no connection with one another. There seemed to be no apparent cause for this sudden and mysterious wave of events. Given the national scale of the incidents, the Japanese domestic intelligence service - the Public Security Intelligence Agency - was quick to take up the task of investigating the incidents. As absurd as it sounds, diligent detective work uncovered that there was one unifying factor between the victims; all of them had been playing the new Pokemon games.

To keep a long story short, investigators found that the music that played in Lavender Town contained ultrasonic audio that, while imperceptible to the ear of a fully-developed adult, could be perceived and registered by children.

The health effects of prolonged exposure to inaudible sound frequencies is well documented. Infrasonic sound - sound below the audible threshold of the human ear - can result in headaches, fatigue, inability to sleep or concentrate, and even altered cardiac functions. In some extreme cases, it can even manifest as paranoia and hallucinations, which lead some to theorize that infrasonic sound is in part responsible for some paranormal phenomenon. Similarly, ultrasonic or very-high frequency waves - sound above the audible threshold of the human hear - can manifest effects such as dizziness, nausea, tinnitus, increased irritability and anxiety, and other deleterious conditions. Prolonged exposure to these frequencies can even possibly permanently damage organ tissue. If these are the effects of inaudible frequences on adults, it’s very possible that the health effects in juveniles could even be more severe.

The PSIA quickly descended on Nintendo and Game Freak’s offices. The investigation discovered an employee of GameFreak had tampered with the audio track for Lavender Town shortly before the game’s final release. Before any arrest could be made or a motive ascertained, the suspect was found deceased at his apartment. Toxicology reports found a lethal amount of alcohol and sleeping medication in his blood.

Nintendo, eager to keep their sterling public reputation, was quick to initiate damage control. The story was largely ignored by the media at the behest of the company’s crowned heads, who paid a small fortune to their friends in the media industry to ensure that it was mentioned as little as possible. Settlements were made with the families of the victims out of court. The records were soon sealed and placed away from the eyes of the public. GameFreak amended the offending track to remove all ultrasonic frequencies, which were not present in any future copies of the game. Despite a widespread recall of the copies that had already been sold, it stands to reason that more than a few of these dangerous cartridges are still in circulation among the second-hand market.

Sounds too outlandish to believe? Well, you’d be right.

The story that I just told you was one of the more famous Pokemon-centric creepypasta’s known as Lavender Town Syndrome. Multiple variations of the story exist, which I combined to give the story a slightly more valid sense of believability6.

One of the most intriguing things about Pokemon is the sheer amount of horror material the fandom has created. There’s an entire genre of creepypasta dedicated to the franchise, with more than a few examples standing as some of the most notorious and well-known specimens of creepypasta. And they’re usually bad. Like, that kind of unique bad that can only be enjoyed by those in the age range of eight and twelve. Ninety percent of them go something like, I bought a conspicuously all-black cartridge that said POKEMON: HELL on it and, like a dumb-ass, played it, and a demonic Pikachu with hyperrealistic eyes crying blood popped up on screen and said SEVEN DAYS. Wat do?

In a way, it’s not hard to see why Pokemon and creepypasta go together like a peanut-butter and banana sandwich with marshmallow fluff; a world so rich with mysterious and dangerous places where children are allowed to roam free and play with dangerous monsters is one that lends itself easily to horror, especially if it’s thought about logically for more than five minutes.

As I mentioned, when the original games released, it was all but impossible to know all the secrets that were crammed into that small, plastic cartridge. Now, as we all know, kids love to make shit up. It’s just what they do. Anyone who, like me, was there for the original release of the first Pokemon games can remember at least one kid in school who just so happened to have an uncle or some distant relative who worked for Nintendo, who’d leaked exclusive insider information about new and upcoming Pokemon titles that only they were privy to.

By the way - I’m still waiting on Pokemon: Rainbow Version, Cole. You fucking liar7.

Given that creepypastas are the urban legends of the internet age, it only makes sense that the enigmatic nature of the early Pokemon games and the many a playground tale that was spun about unknown Pokemon, terrifying glitches, and cursed game cartridges would be a match made in Heaven. Or Hell, in this case.

I could go on about my own experiences with these elementary school urban legends and the playground hucksters that spun them, or even cover some of the other Pokemon creepypastas in depth, but there’s really only one more I feel like I have time to cover here before I draw this article to a close.

I like this one in particular because it, like the more elaborate variations of Lavender Town Syndrome that include more details that create an air of authenticity, seems like something that could actually happen.

It’s Japan. 1997. December 16th. At 9:59 PM, NHK General TV in Shibuya, Tokyo, is the first news station to broadcast the breaking story that children across the country are reporting to hospitals, wracked with sudden, violent, and inexplicable seizures.

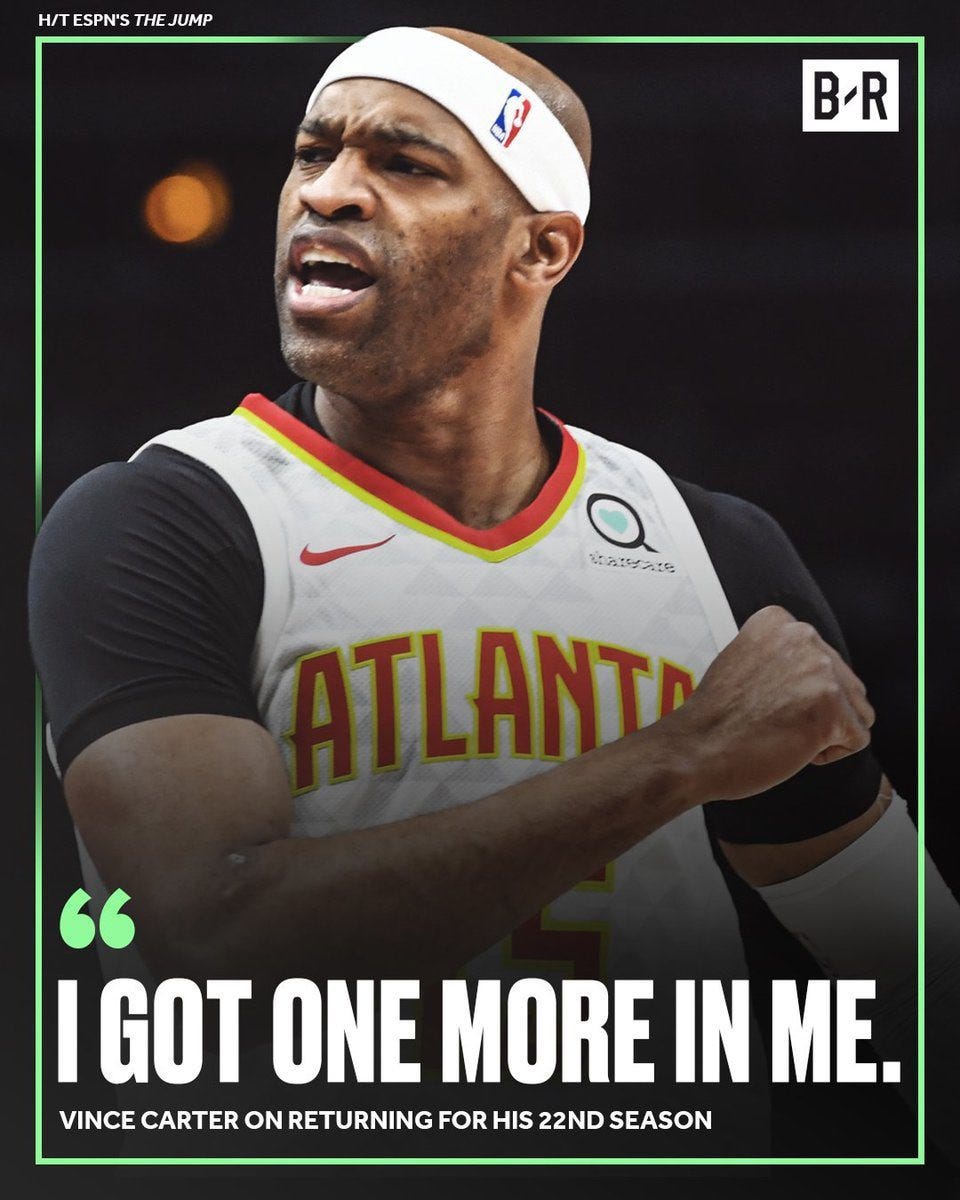

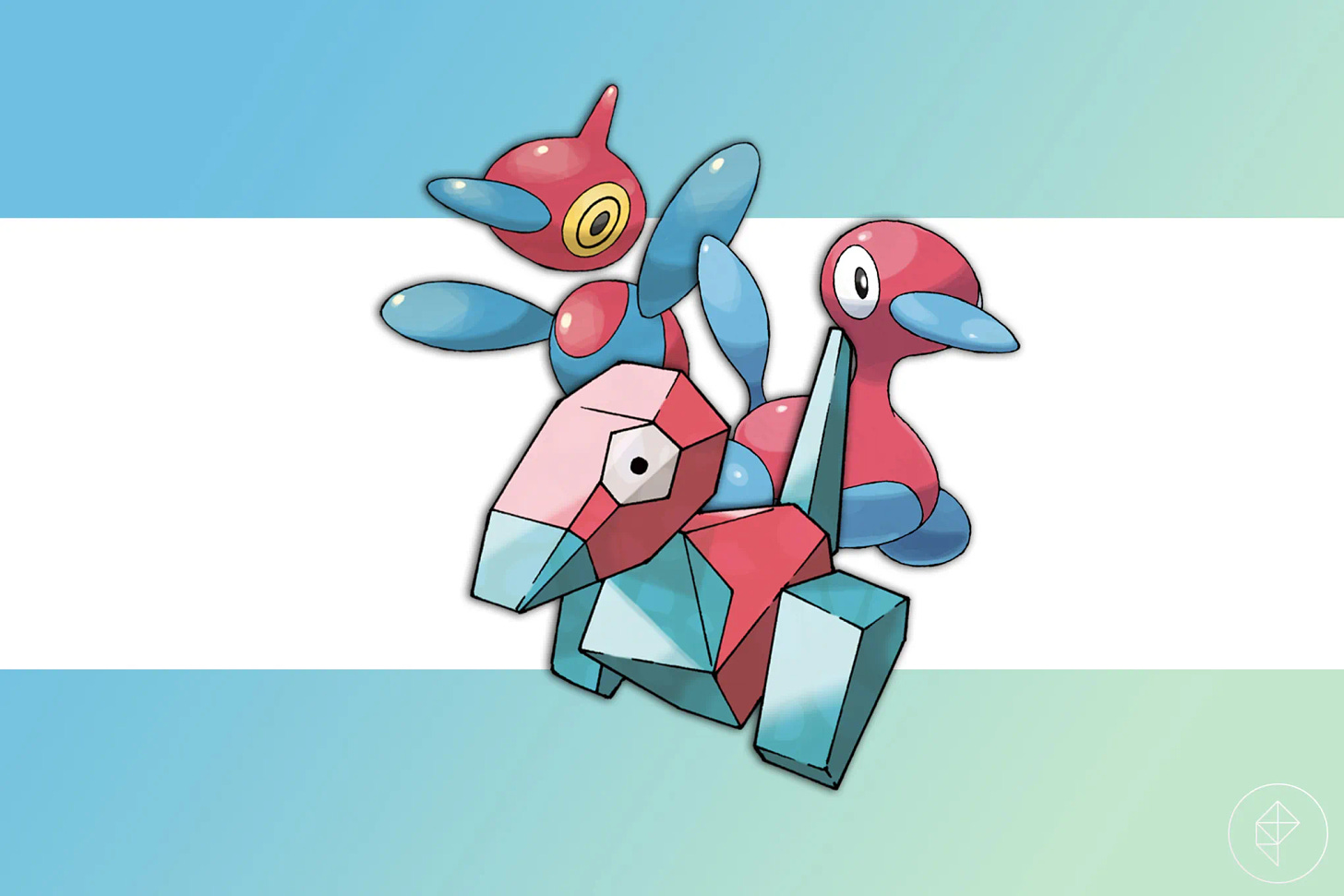

The source of the phenomenon was quickly pinpointed as the airing of a new episode of the wildly popular Pokemon anime on Tokyo TV. With the series enjoying the apogee of its popularity, the episode was broadcast to over thirty networks across Japan, and viewed by a record-breaking 4.1 million households. This episode, the 138th of the series, was called Denno Senshi Porygon - or Electric Soldier Porygon in English. This episode just happen to feature a sequence in which brightly colored strobing lights flash on screen.

Now, what tends to happen to certain photosensitive people with a little condition we call epilepsy when exposed to bright, strobing, colorful lights?

A staggering total of six-hundred and eighty five people were admitted to hospitals nation-wide over the course of three hours, suffering from these mysterious seizures. And those were just the victims who were admitted to the hospital by way of ambulance. The exact number of victims is unknown, but it is estimated that a total of twelve thousand people suffered minor effects. The overwhelming majority of victims were between the ages of eleven and fifteen, though, several adults were reported to have been effected as well.

Does this story sound a little more realistic than Lavender Town Syndrome? That’s because it is.

Denno Senshi Porygon was a very real episode of the anime that really did put almost seven hundred people in the hospital. Fortunately, unlike the fictional Lavender Town Syndrome, no one was seriously harmed, and the total body count is comes out to zero.

The Japanese media would go on to dub the incident Pokemon Shock. The following day, TV Tokyo broadcast a public apology for their part in airing the episode. An investigation of the studio that animated the Pokemon anime, OLM Team Ota, was ordered by the Japanese National Police Agency, resulting in the production being brought to a halt for over four months. Nintendo took a hit to their stocks by over 3%, and, for their part, denied any responsibility because, hey - they only made the games, not the animated series. Many fans of the show - even a handful of victims - wrote letters to both the studio and the Japanese police, pleading for the program not to be cancelled.

Though the show would resume, Denno Senshi Porygon would be pulled from syndication. To this day, it has never been aired again. Not in Japan. Not anywhere. The featured Pokemon of the episode - the eponymous Porygon - nor its evolutions have been featured in the anime again. Which feels deeply unfair, given that, in the episode, it was Pikachu that caused the flashing lights, not Porygon. Unfortunately, as Pikachu is the face of the franchise, poor Porygon was forced to take the fall for the little rat bastard.

One can only hope that once Porygon is done with his quarter in the clink, Don Pika gives him some generous reimbursement for his services to la famiglia.

To this day, this incident holds the dubious honor of possessing the Guiness World Record’s title of Most Photosensitive Epileptic Seizures Caused by a Television Show.

As I’ve said several times throughout this, there’s a lot more about Pokemon I could say. The games. The anime. The fandom and culture surrounding it. The well is deep, broad, and quite possibly filled with enough material to keep me writing for the rest of my natural life. But, given the Halloween season is nearing it’s zenith, I figured we’d just take a lot at just one spooky urban legend about the game, and the real life incident that may have inspired it.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, literally just as I finished this article up, a GameFreak employee fell for a phishing scam over the weekend and over a fucking terabyte of almost two decades of internal development files, documents, artwork, and code were hacked from Nintendo. While I’m pretty sure the employee responsible is probably in the process of burning down his house and securing a fake passport to flee Japan - assuming the elite band of ninja assassins Nintendo no doubt dispatched to appropriately punish them hasn’t gotten to them already - the internet has been getting a good kick out of their misfortune. It turns out that some employees in their ranks has been hard at work for the past decade putting the freak in Game Freak8.

It’s probably worth going into at some point, if only because it’s so bizarre. I mean, they leaked internal documents revealing that apparently GameFreak has been sitting on an official creation myth for the Pokemon universe that was just a little too strange to reveal to the public.

Given that the entirety of the information uncovered in what’s going to be known to posterity as the #TeraLeak is still being processed, we’ll have to save it for another time. Who knows what information may be squirreled away deep in the annals of GameFreak’s records… perhaps they just might find a certain track from Pokemon: Red and Green, uncut. Unedited. Unadjusted.

Just as it was always intended to be heard…

Or maybe they’ll just keep finding more stories like this one.

That might just be the real story Nintendo didn’t want anyone to know.

Who knows?

And yes, Pikachu of the anime is male. I had to confirm this.

Three billion dollars of this alone comes from a lucrative partnership with various Asian airline companies known as Pokemon Jets, which are commercial airliners kitted out with Pokemon-themed livery and themed to offer an all-inclusive Pokemon experience. I am not making this up.

Again, the over-all quality of the games, from the programming to game play to design, can be mapped out in a perfect parabola curve, as during the fourth and fifth generations GameFreak had largely gotten their programming issues under control, only for them to apparently give up and go back to not giving a fuck.

And yes, we can all laugh at the absurdity that the player-character being canonically ten years old and being sent out by his negligent mother and absentee father to go on a cross-country trek to domesticate fire-breathing dragons and dinosaurs. But that was 90’s parenting for you, I guess.

Though Japan has a reputation for absurd rates of teenage suicide due to several highly publicized incidents, the teenage suicide rate in the country is actually below the international average.

For instance, the involvement of the Japanese domestic intelligence agency and the mention of a disgruntled employee were absent from the original text, but added in other variations of the story.

Of course, I was smart enough to know Cole was lying through his fucked-up teeth, but everyone else at school uncritically accepted that his uncle just happened to be John Nintendo who gave him a copy of an unreleased Pokemon game.

Concept documents pitching and developing gym leaders for Generation V reveal that someone on their staff was very much into latinas, big mama’s, and Pam Grier. Their words, not mine.

Thanks for the interesting read! It reminded me of the legend of the “Polybius” arcade game, which was also said to cause seizures and paranoia. The legend said it was created by the CIA to test sinister technology, and was surreptitiously placed in arcades by nameless Men In Black. I’m sure it has plenty of associated creepypastas…

I remember when the Pokemon craze swept through the little town I lived in at the time. It was a pretty distinct divide of the "normal" kids and us loser nerds who did stuff like play video games and D&D, read fantasy books, and watch anime. (I also remember when we called it "Japanimation" because that cringe was the term of the time.) A couple of my best friends already had the Cadillac-sized original Game-Boy when the games released, so each got a copy of Red and Blue respectively for their birthdays. I got in on it a bit later, after the Game-Boy Color released near the end of that year. Christmas rolled around and I'd gotten a lime green GBC, a stack of crazy attachments, (the screen magnifier with the build in light was great, the crappy joystick that clipped over the d-pad not so much) a copy of Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening, and naturally, Pokemon Yellow.

Kids these days can call me a "Genwunner" all they want. They haven't, but they can, and I won't care. My time with the series lived and died in Gen I, both in terms of the video games, the show, and the TCG. They were fun for what they were, but the time in which this series came to establish a foothold in my life was one in which it would soon find itself competing against far better options.

Final Fantasy VII and Breath of Fire III held my attention in the JRPG world, followed a few short years later by the first Xenosaga on the PS2.

The Pokemon show was swiftly cast aside for the Toonami block once we moved out of the mountains and back to the city, where Cartoon Network was no longer sharing a channel with ESPN. Yes, weird as it sounds, Cartoon Network and ESPN shared the same channel in the town I grew up in, swapping over right at 4:00 PM, when Toonami was set to start. Suddenly, DBZ and the various animated superhero shows of the day were now open options for me, so Pokemon was soon cast aside.

And where the TCG is concerned, well, it's a bit of a surprising one. You might think, "Ah yes, it must've been Magic: The Gathering." You'd be right to assume I played it then, too, but I found MtG before the Pokemon TCG, and my core friend group played Pokemon more. However, our interest in that game was ultimately pretty short lived considering that, largely because of my best friend's stepdad, each of us had a massive collection of cards for the WildStorm Comics TCG that was, at the time, put out by Image. The game primarily featured characters and goons from the WildCats comic series, but also featured the likes of Savage Dragon and Spawn, so you can imagine why a bunch of nerdy teenage boys like us would flock to that over Pokemon. This was to say nothing of the deeper strategy involved with that game's deck building. Believe me when I say that we would spend hours upon hours refining our decks whenever we threw our little tournaments with each other.

Still, though short-lived, Pokemon did have a pretty big impact in my youth. Big enough that even living in a tiny tourist town in the California mountains with a population of a scant couple thousand, half of whom were retirees, my friends and I all still heard about the Porygon episode. Funny how that works.